HARPSWELL — Doug Johnson’s wife knew he’d never be happy alone.

“She told me, she said, ‘If I go, it’s okay to be with somebody else,’ ” he said, choking on the memory from the day his wife died in September.

A month later, he stopped by to check on Flo Rich, an old acquaintance he heard was home recovering from a heart operation. He didn’t know she’d lost her

husband to lung failure six years earlier – or that she’d be the one his wife was talking about.

As they caught up over coffee, he casually asked if she ever thought about getting married again.

“She told me, she’s doing fine, she’s become very independent, wasn’t really looking for anyone,” said Johnson, 72.

She hiked with her friends, did yoga and played bridge.

But in the back of her mind, Rich, 80, said, “I always thought it might be nice.”

Relationships have proven to have a positive impact on health and mortality, for reasons ranging from getting reminders about taking medicine to having

greater purpose in life, said Harry Reis, a psychology professor and author of the Encyclopedia of Human Relationships.

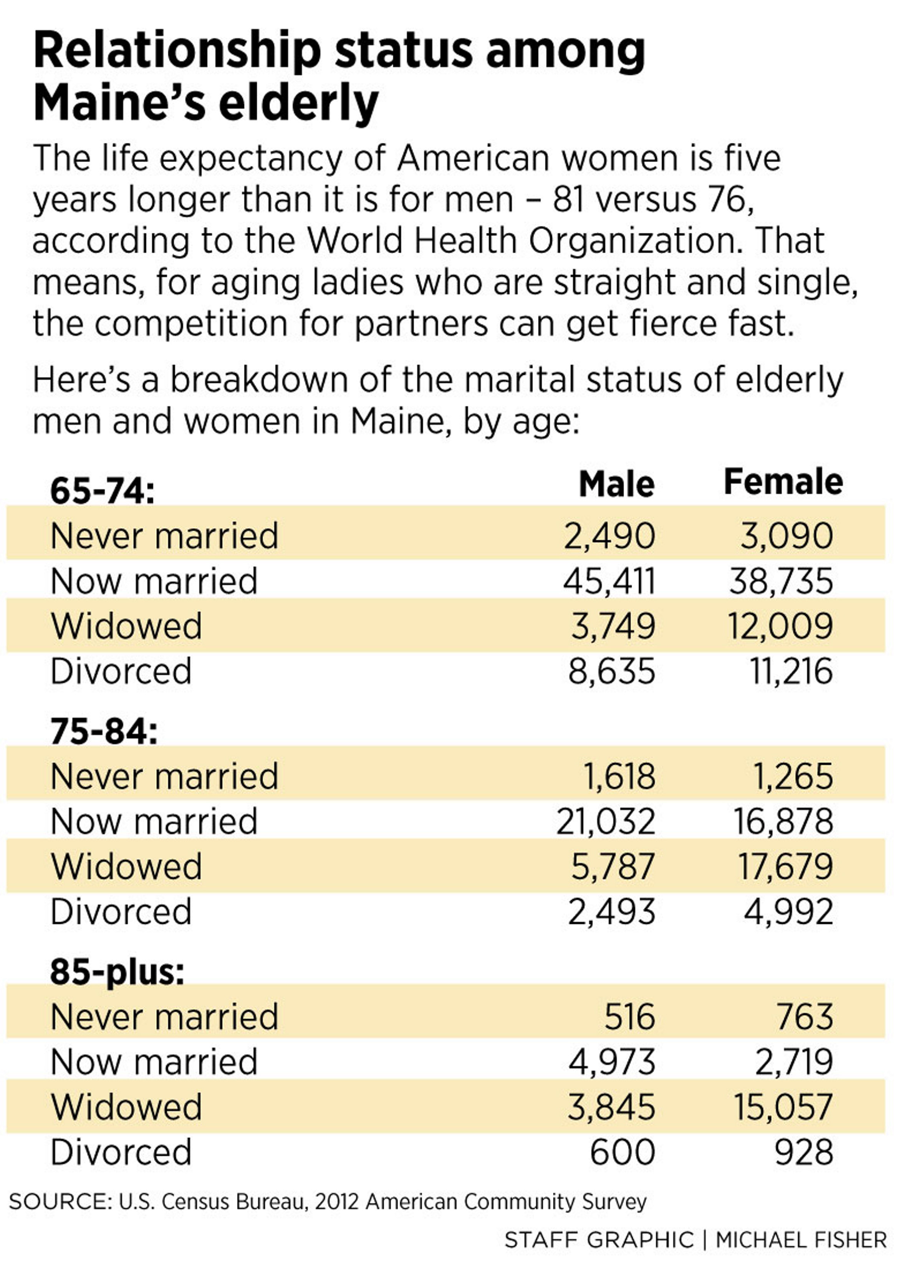

But more people are entering old age unattached than ever before. Thirty percent of baby boomers aren’t married, compared to 20 percent

for the same age group in 1980, said Susan Brown, a sociology professor from the Center for Family and Demographic Research at Bowling Green State

University in Ohio. The trend holds true in Maine, where 34 percent of people age 50 to 64 were single, widowed or divorced in 2012, up from 23 percent in

1990, according to U.S. Census data.

Although falling in love later in life could add years of bliss for elderly couples, often it’s complicated. There can be guilt about moving on from a

longtime spouse, wills that need updating, assets to sort out and children whose acceptance can bring its own set of complications. Because of those snares

– and greater acceptance of unmarried partnerships – fewer new elderly couples are choosing to wed and, instead, figuring out what legal and living

arrangements best suit their relationship.

memories of the past

Johnson and Rich first met when they and their spouses found themselves on the same side of a debate over a liquefied natural gas terminal proposed in

Harpswell.

Both couples had retired to the midcoast town a few years earlier – but took much different routes to get there.

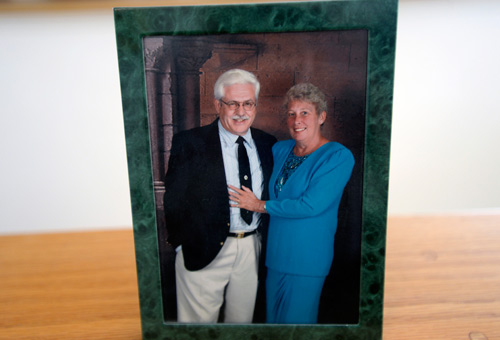

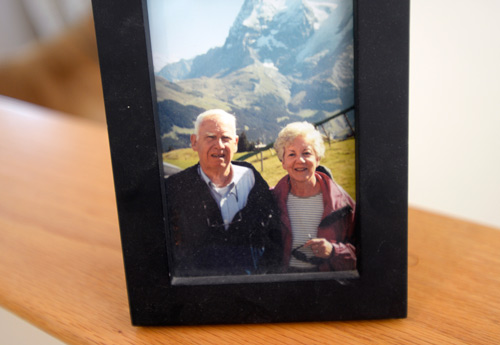

Before they began dating, Flo Rich and Doug Johnson had both lost the spouses who had been their lifelong partners. Flo and Wally Rich, above, had lived all over the country, from New Hampshire to Hawaii, before settling in Cundys Harbor in their 60s. He died in 2007. Doug and Linda Barnes Johnson, below, lived in the same house in Connecticut for four decades. She died last September.

Family Photo

Family Photo

Johnson, who grew up in Connecticut, met his wife, Linda Barnes, in high school. They both worked at the local A&P supermarket.

“In the second year of school, we started to go together, and I never went with anyone else,” he said.

They got married and she got pregnant. Johnson, who went to school for industrial electronics, soon landed a job at an aerospace company, where he worked

until he retired.

Johnson and his wife lived in the same house in Connecticut for 40 years. Rich and her husband moved 33 times before coming to Harpswell.

She was a stewardess living near Boston, when Wally Rich showed up outside a friend’s apartment in an Oldsmobile convertible and she got in the front seat.

He had come down to the city from Maine, where he grew up and had just finished college, to pick up his uniform for the Marine Corps.

They spent the summer together before he left for training at the base in Quantico, Virginia. She put in for a transfer to Washington, D.C., and a couple

months later, they got married.

When he returned from a deployment to Japan, they moved into his mother’s house in South Portland, then moved all over the country, from New Hampshire to

Hawaii, working jobs in restaurants and real estate, before buying a small house in Cundys Harbor in Harpswell in their 60s and settling down.

When the debate over a controversial liquefied natural gas terminal swept over the town in 2004, the Johnsons and the Riches both joined the group

supporting the proposal. They sat together at town meetings and held signs by the side of the road. After residents took a vote to reject the terminal, the

two couples mostly lost touch.

Neither Johnson nor Rich knew that each other’s spouses had died, when he stopped by to wish her well her last fall.

At first, Rich didn’t think much of the visit, other than that it was nice.

But he kept coming back.

One day, he brought flowers with him and that’s when she knew.

Their first date was to Applebee’s with a married couple with whom Johnson and his wife once went out almost weekly.

The husband thought Rich was too old. The wife thought it was too soon.

Although Johnson had been a widower for a shorter time than Rich had been a widow, the feelings came “pretty quick,” he said.

Men are more likely to want to find a new partner, said Brown, the Bowling Green sociologist, “because they know that they’ve benefited greatly from the

care that their wife provided them with,” as opposed to the “been-there,-done-that kind of attitude” more women have.

It’s important, however, for people who have lost a spouse, in death or divorce, to properly grieve before entering into a new relationship, said William

Jeanblanc, director of geriatric psychiatry at Maine Medical Center.

“But at the same time, people need people and love is what makes life of value,” he said.

in their words

an interview with Doug Johnson & Flo Rich

‘blending the children’

Despite the judgment of their peers or family members, who might feel a new relationship is a betrayal of the last, “ultimately people have to choose

what’s best for them,” Jeanblanc said.

Rich said she never spoke with her husband about what she should do if she outlived him.

“I guess we thought we’d always be together,” she said. “We didn’t have that many serious conversations. We were always on the go.”

Even though Johnson’s wife had given him her blessing, he said, “I still felt a little guilty at the time.”

He and Rich kept seeing each other anyway and started spending nights together. He’d bring his dog with him or she’d bring her cats to his place.

That’s when it dawned on Rich’s daughter.

“ ‘Oh, wait a minute, they’re blending the children. This is getting serious,’ ” Kim Rich said she remembers thinking, and laughed.

Soon enough, they got tired of going back and forth, and she moved in.

Kim Rich said she worried at first that some of her more religious relatives would judge her mother.

But “they were the first to say, ‘People in my church, they do that all the time,’ ” she said.

Johnson and Rich want to get married but agreed, for financial reasons, it doesn’t make sense. Rich receives a pension and free medical care because of her

late husband’s military service. She’d lose that if she wed Johnson.

“What if something happened to me the next day?” he said.

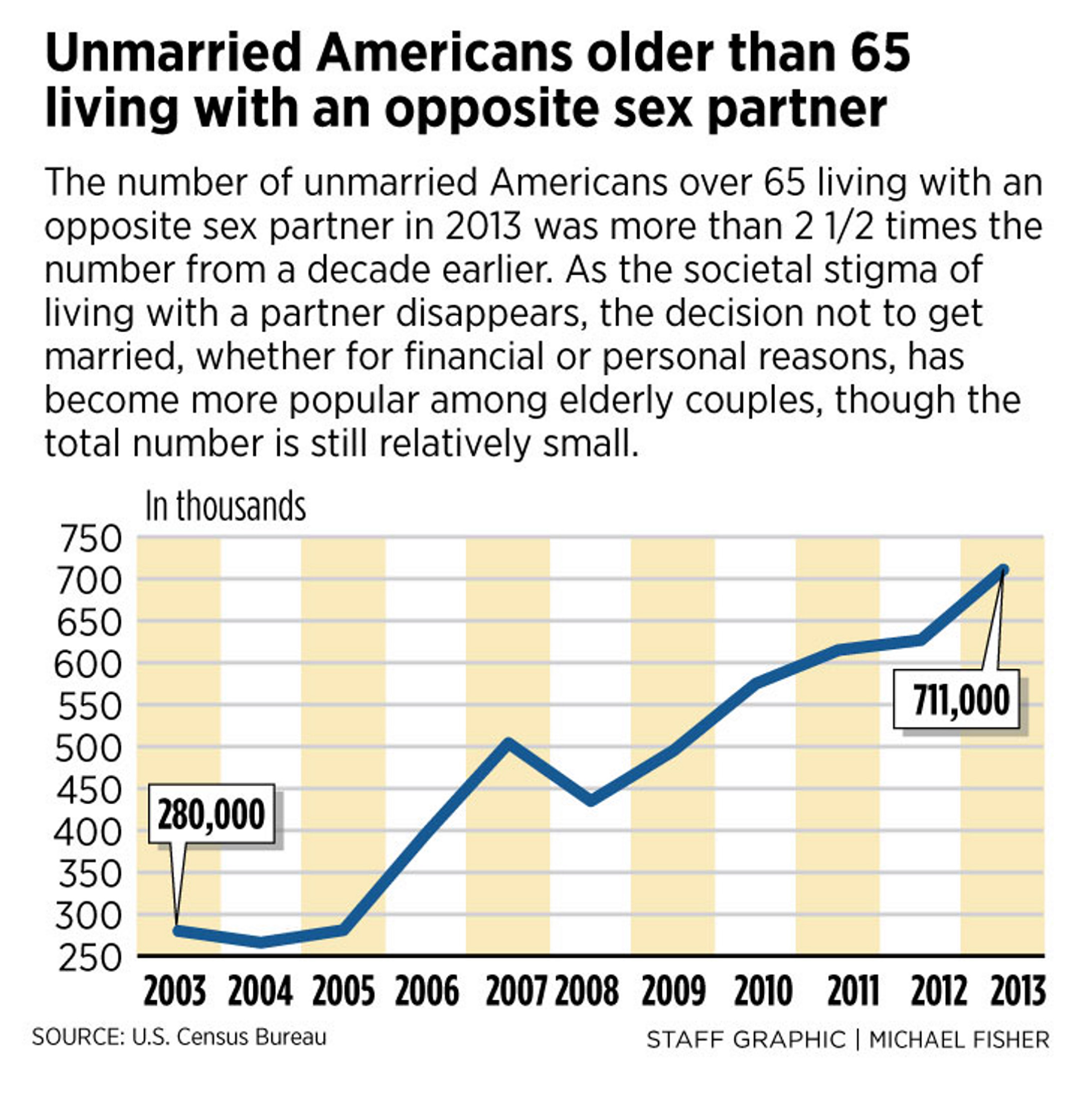

The number of elderly American couples living together without getting married is on the rise. Last year, 711,000 unmarried people over 65 were living with

an opposite-sex partner, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s more than 2 1/2 times as many as a decade earlier.

“It’s lost nearly all of its stigma,” said Brown, the sociologist.

Victoria Powers, an elder law attorney in Portland, said there are some people whose value systems dictate that they marry, so they make prenuptial

agreements to ensure that their assets are passed on to their own children. Other times, she said, people who have been married before don’t have a desire

to do it again, but want their partner to have the same rights as a spouse would.

Johnson wants to make sure Rich has a place to live if he dies before she does. So, they’ve been working with a lawyer to grant her the right to stay at

his house, and have the money to keep it up, as long as she’s alive. After that, it would get passed on to Johnson’s son, and Rich’s daughter and son would

get whatever she leaves behind from her marriage to their father.

Children can often be the greatest complicating factor when it comes to legal issues surrounding older adults in new relationships, said Powers.

That doesn’t just have to do with inheritance, she said, but also with who make decisions about their parents’ health and what happens to them after they

die. Often, when someone falls seriously ill before they’ve sorted out those issues, the spouse and children end up in court, Powers said.

That’s not the case for Johnson and Rich, whose children have been supportive of their relationship all along.

“I actually feel a sense of relief,” Kim Rich said. “I tended to worry a lot more about my mom living alone. It’s so nice to know that she and Doug are

taking care of each other.”

‘the light’ has changed

Their two families will come together for a commitment ceremony this summer on Sebago Lake, though Johnson and Rich say they already consider each other

husband and wife.

She stops him from eating too many sweets and cuts him off when he’s getting long-winded.

He makes her laugh and feel loved, and, occasionally, he cooks a meal.

Doug Johnson and Flo Rich enjoy a dinner with family and friends at their Harpswell home. To the right is Flo's daughter Kim Rich.

by Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

by Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Staff Photographer

On a recent Friday, he made his specialty, fish chowder, at a dinner party they hosted for Rich’s daughter and her husband and another couple Rich met

playing bridge.

As Johnson’s dog, Barney, scratched at the porch door, the couples talked about their pets and how high their rhubarb plants had gotten. They told stories

about places they’d traveled and wildlife they’d seen, while they spooned their chowder and sipped on Pinot grigio from plastic cups. Johnson sat at the

head of the table and Rich cleared plates as the guests finished each course.

The couples visited for a while after dinner. By the time the guests left, Johnson and Rich were ready for bed.

They went upstairs to their room, where Rich keeps a picture of her husband on the bureau. It doesn’t bother Johnson, just as she’s fine with the vial of

his wife’s ashes that he wears around his neck.

They’re always asleep before 9 p.m., Johnson said, and he always wakes up first, long before sunrise.

For a while, after his wife died, when he opened his eyes in the morning, he would see a white light through the center of the skylight above the bed. “It

wasn’t the moon and it wasn’t a star,” Johnson said.

He had asked his wife to be his guardian angel and has his own ideas about what it was.

Sometime after he reconnected with Rich, he noticed it changed.

There’s still a light in the morning, he said, but it’s off to the side and less defined.

“It’s not the same one that was there before, but there’s still a light,” he said.

Part VII: Mildred Rood

Maine doesn't make it easy

The demand for home care – already unmet – is poised to explode as the state’s population propels into old age. Why, then, are programs that keep low-income seniors out of nursing homes so badly underfunded and how can we attract enough caregivers with such a meager wage?

Seniors in love

The search for intimacy in assisted living

Discovering new love interests in a communal setting comes with its own set of challenges, namely 'there's not a whole lot of privacy.'

Further Discussion

Here at

PressHerald.com we value our readers and are committed to growing our community by encouraging you to add to the discussion.

To ensure conscientious dialogue we have implemented a strict no-bullying policy. To participate, you must follow our

Terms of Use.

Questions about the article? Add them below and we’ll try to answer them or do a follow-up post as soon as we can.

Technical problems? Email them to us with an exact description of the problem. Make sure to include:

- Type of computer or mobile device your are using

- Exact operating system and browser you are viewing the site on (TIP: You can easily determine your operating system here.)