FALMOUTH — Barbara DeWaters spent her last days pretty much as she had planned them.

Her five children were gathered around her hospital bed, set up in an enclosed side porch at the family’s camp on Highland Lake. Outside, ducks quacked

along the shore in dappled August sunshine. Boats rested at the dock in a weekday lull.

At 92, the matriarch of the DeWaters family neared the end of a three-month battle with brain cancer, cared for by her children with help from Hospice of

Southern Maine. Though she tried to make it uncomplicated for her kids, her passing had evolved into an emotional experience that none of them would soon

forget.

After saying her goodbyes and tying up loose ends in recent weeks, she mostly slept now. Her hospice aide had just finished her morning bath. A small lamp

cast a warm glow on the watchful faces at her bedside. The conversation was quiet, measured.

“You’re looking real pretty today, Mum,” said her eldest, Rick DeWaters, 67, a retired special education teacher.

“We love you, Mum,” said Jan DeWaters, 53, an engineering professor who’s still known as the baby of the family.

Barbara DeWaters kneels while holding a pet cat in front of her family’s camp on Highland Lake in Falmouth around 1940.

Contributed Photo

Newlyweds Barbara and Frederick DeWaters, a Navy petty officer during World War II, celebrate their honeymoon in Boston in May 1945.

Contributed Photo

The frail, older woman responded without opening her eyes.

“I love all of you,” she said.

It was one of the last times she spoke to her children. By the next morning, she was gone, leaving a void in the DeWaters family that will never be filled.

As difficult as it was to witness their mother’s death, the DeWaters siblings say the experience was made easier and more meaningful by Hospice of Southern

Maine, a nonprofit agency that provides hospice care in Cumberland and York counties.

Over the course of 72 days, a dedicated hospice aide, registered nurse and social worker visited Barbara DeWaters regularly in her home as she needed them, assisting her with everything from bathing to accepting the loss of independence that comes at the end of life. Sometimes the process was difficult, despite a granite resolve that runs in the family. Hospice workers helped the siblings wade through a variety of medical and emotional challenges and face the experience together, on their own terms and exactly where they wanted to be.

“We could not have done this without hospice,” Jan DeWaters said later, sitting on the screened front porch, overlooking the lake.

But while the DeWaters family had a positive experience with hospice care, many older Mainers and their families will have a hard time ensuring that they

get a similar quality of care. And the problem threatens to grow worse as Maine’s senior population expands and the use, cost and abuse of Medicare-funded

hospice services increase across the nation.

There’s no easy way to find or choose among the 19 Medicare-certified hospice agencies spread across the state. State agencies and advocacy groups avoid

recommending one hospice agency over another, and survey and inspection reports for state licensing and Medicare certfication aren’t readily available to

the public and likely wouldn’t be especially helpful or meaningful to the average consumer.

Moreover, many Mainers have little choice in selecting hospice care because some rural communities are served by only one Medicare-certified provider, including in Aroostook, Washington and Piscataquis counties.

“Access is a huge issue in Maine,” said Kandyce Powell, executive director of the Maine Hospice Council & Center for End-of-Life Care. “Even if people

know what services to ask for, they may not be able to get them.”

-

WHAT IS HOSPICE?

HISTORY: The first hospice facility opened in the United States in 1974 and Congress created a Medicare hospice benefit in 1982, expanding it to cover terminally ill patients in nursing homes in 1986.

MISSION: Hospice agencies provide medical, social, emotional and spiritual care at the end of life, whether in a private home, assisted-living facility, nursing home or hospital.

THE TEAM: A typical hospice team includes a doctor, registered nurse, health care aide, social worker, chaplain and volunteers who are knowledgeable and comfortable talking about end-of-life issues.

THE TASK: Hospice caregivers work with a person’s primary care physician and family caregivers to provide optimum care for life-limiting illnesses, including Alzheimer’s and other related dementias.

WHAT’S COVERED: Hospice care is an elected benefit under Medicare that covers medications related to a terminal illness, services provided by a hospice team and durable medical equipment. MaineCare and private insurance also cover hospice care.

THE DURATION: Hospice care usually is provided for as long as six months, but it may be extended if certain guidelines are met.

Problems in the hospice industry likely will get worse as demand for quality end-of-life care grows along with a rapidly aging population. Maine’s median

age – 43.9 years – is the highest in the United States, in part because the state also has a dwindling younger population, according to the U.S. Census.

The state’s proportion of people age 65 and older – 17.7 percent – is second only to Florida’s 18.6 percent.

Maine also has the nation’s highest proportion of baby boomers – 29 percent of its 1.3 million residents were born between 1946 and 1964 – and they’re

turning 65 at a rate of 18,250 a year, according to AARP Maine. By 2030, more than 25 percent of Mainers will be 65 or older, magnifying the already

serious challenges facing seniors and their communities.

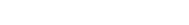

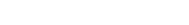

At the same time, Medicare, which funds 87 percent of all hospice services in the United States, has already seen exponential growth in hospice use and

costs in Maine and nationally, according to Hospice Analytics, a research and consulting firm in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Medicare-funded hospice use in Maine increased 36 percent from 2000 to 2012, compared to 24 percent nationally. During the same period, the annual cost of

that care increased more than 13 times in Maine, from $4.5 million to $59.8 million, compared to five times nationally, from $2.9 billion to $15 billion.

Such massive growth, attributed to expansion of the Medicare-funded hospice industry and greater awareness of its multiple benefits, has drawn increasing

scrutiny from Medicare, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and national media.

Recent reports by The Washington Post and other major news outlets have offered harrowing stories of Medicare fraud and hospice patient abuse, including

examples of some providers that colluded with long-term care facilities to enroll patients who didn’t need hospice care. The reports have focused on

for-profit providers and highlighted infrequent Medicare certification as a significant problem.

Congress passed a bill in September that calls for Medicare certification surveys to be done every three years instead of every 6.5 years, as previously

directed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. But more frequent hospice surveys that focus on filling out bureaucratic reports will do

little to help terminally ill people and their loved ones ensure that they get quality end-of-life care.

“It’s a simplistic approach to the complicated issues of waste, fraud and abuse,” said Cordt Kassner, chief executive officer of Hospice Analytics and

former head of the Colorado Center for Hospice & Palliative Care.

NO EASY WAY

Barbara DeWaters learned that she had brain cancer in May, after spending several weeks in rehabilitative care at The Cedars skilled-nursing facility in

Portland. Her doctor wasn’t specific about how much time she had left. A few months, at best.

Her children at her side, Barbara DeWaters lives out her final days at her family’s camp in Falmouth, thanks in large part to the freedoms and comforts afforded her by Medicare-funded hospice care. Here, hospice aide Cindy Higham, far left, rubs lotion on her feet as Barbara’s family gathers around her. Her children, from left, are Barbara Leighton, Jan DeWaters, Julie Duffy, Rick DeWaters and Jere DeWaters.

Contributed Photo

She and her children decided she would move into Birchwoods at Canco, a nearby assisted-living facility. There she would have help managing her medications

and be able to join social activities such as playing cards and dining with other residents.

She also knew she would need hospice care. She was familiar with its benefits. She and her husband, Frederick, had retired to Florida after operating a

plumbing and heating company in Portland for many years. When he became terminally ill in the late 1990s, hospice workers helped her take care of him.

The DeWaters children also had experienced the benefits of hospice care with other family members. So, when their mother got sick, they contacted Hospice

of Southern Maine.

“The people at Cedars recommended it,” said Barbara Leighton, 66, the oldest daughter, who retired from Unum and lives in Westbrook. “They said if Mum ever

had to go to the hospice house, she would be cared for by people who had already been working with her.”

The DeWaters family knew more about hospice than many Mainers do before they choose a provider. Right now, the recommended approach is to get a list of

local hospice providers, seek recommendations from family members, friends, doctors and others, and call around to learn how each agency offers services.

One major deficit in the search for end-of-life care is the lack of a federal online registry of hospice providers, like Nursing Home Compare, a

Medicare-sponsored website that rates facilities based on various quality measures and posts recent inspection reports. Without a similar website for

end-of-life programs, consumers must search the Internet for local hospice options and request inspection reports under the Freedom of Access Act.

“I’ve been advocating for a hospice search website for years,” said Powell, head of the state hospice council. “It would give consumers a basic platform to

find out about providers in their area.”

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 calls for collecting and reporting quality-of-care information about hospice providers on a

searchable website. It would calculate quality based on several measures, from assessing pain levels to addressing patient beliefs or values. It would

include data provided by hospice agencies and feedback from patients’ loved ones.

But CMS started collecting data from hospices only in July, and a “Hospice Compare” website isn’t expected to be up and running before 2017, said Kassner,

the hospice expert. A notice on the CMS website says “no date has been specified to begin public reporting of (hospice) quality data.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s 2020 or later,” Kassner said.

COST-SAVING CARE

Before Barbara DeWaters moved to Birchwoods in Portland, Hospice of Southern Maine delivered a hospital bed, a wheelchair and a therapeutic lounge chair to

her apartment. Then hospice staff members met with her to talk about services available under Medicare, which pays hospice agencies about $155 per patient

per day. It was a bit overwhelming for her at first.

“They were on board from the get-go, but it appeared to Mom that they were taking over her life,” said Rick DeWaters, who lives in New York. “She was

concerned that hospice would interfere with her living, and they absolutely understood it.”

Hospice workers allowed Barbara DeWaters to access services as she needed them. At first they mostly monitored her health and coordinated her pain

medication and other prescriptions. Much of her care was provided by her children. Jan and Rick DeWaters left their families in New York to join their

siblings’ effort.

When Barbara DeWaters could no longer bathe herself, Cindy Higham, a hospice aide, started visiting a few days each week, then daily as the need increased.

Eventually, she also helped with toileting. As barriers fell and the two women became friends, she provided emotional support for the entire family.

“My mother loved Cindy,” said Jan DeWaters, who teaches at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York. “She became like family to us. She was a spiritual

healer. She helped her face the decision every morning: ‘Is it time to give up or is it time to give it another day?’ She taught me how to talk to my

mother about what we were going through. Cindy did that for all of us.”

Barbara DeWaters struggled a little to come to terms with her death. Sometimes she seemed angry, distrustful, afraid. Near the end, conversations with her

children grew intense.

“She said, ‘I don’t want to leave you,’ ” recalled Julie Duffy, 55, the second-youngest, who lives in Westbrook and works at Unum. “I said, ‘You’re not

going to leave me. You’re always going to be in my heart.’ ”

Edie White, a social worker, helped the family, too.

“There was a lot of trust that developed between her and my mother,” Rick DeWaters said. “They talked about the death experience and a lot of other things.

It was hard for us to discuss the honesty of what was going to happen, but it became easier for us because of Edie.”

At $155 per day, Barbara DeWaters’ hospice care cost Medicare just over $11,000, about the midpoint of the state and national averages of $10,075 and

$11,842, respectively.

As word has spread about the various benefits of hospice care, so has its use, especially in Maine.

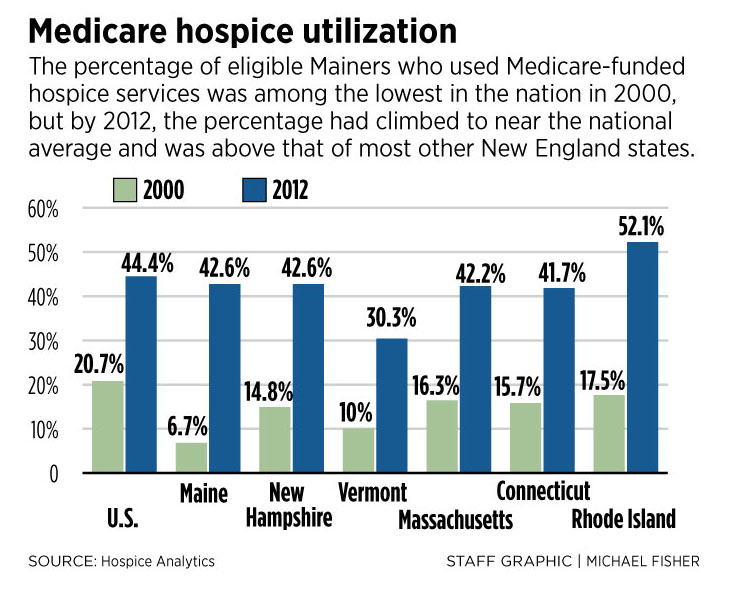

From 2000 to 2012, Maine’s utilization rate went from 6.7 percent to 42.6 percent of Medicare deaths, propelling the state from 49th to 28th in the nation,

according to Medicare data analyzed by Hospice Analytics. In that period, the national average use of Medicare-funded hospice services increased from 20.7

percent to 44.4 percent.

End-of-life experts say the increased use is good because it reduces the need for more costly hospital care. Hospice saved Medicare an average of $2,561 to

$6,430 per patient, depending on the overall length of care, according to a 2013 Health Affairs report analyzing claims data from 2002 to 2008.

“Instead of attempting to limit Medicare hospice participation, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should focus on ensuring the timely

enrollment of qualified patients who desire the benefit,” the report concluded.

‘WHEREVER YOU ARE’

As Barbara DeWaters’ health declined, her children talked increasingly about letting her spend her final days at the lake, in the camp that has been the

center of family gatherings for five generations. After several daytime visits, when she enjoyed spending time with many of her 14 grandchildren and six

great-grandchildren, they decided to make it happen. They asked her caregivers from Hospice of Southern Maine if it could be done and got an eager

response.

In early August, the agency moved the hospital bed from her apartment at Birchwoods to the camp’s enclosed side porch. They put her therapeutic recliner on

the screened front porch. The hospice aide and registered nurse, who were visiting regularly now, drove into the countryside beyond Portland.

In her remaining days, Barbara DeWaters reminisced with her kids, ate ice cream on warm afternoons and sipped beer on the front porch. Her eyesight was

gone, but she could feel the breeze and smell the pines and remember swimming in the cool water, sitting on the dock and reading a book, and going for boat

rides with her husband.

“She really couldn’t see the lake anymore, but I believe she had seen it so many times before that she could see it in her mind,” Barbara Leighton said.

“That was such an amazing gift for her and for us. If there’s one thing I would say to people, it’s to let hospice handle it. You’ve got enough to worry

about. They go wherever you are.”

In 2012, 57 percent of Medicare-funded hospice deaths in the United States occurred in private homes, while 24 percent were in nursing homes, 17 percent

were in assisted-living facilities and 1 percent were in hospice facilities, according to Hospice Analytics.

Edie White, the social worker, said hospice caregivers are experts in managing a dying patient’s needs, especially symptom and pain relief, as well as

offering physical, emotional and spiritual comfort. For Barbara DeWaters’ kids, comfort included moving her to the camp.

“It’s not a bad place to end your life,” said White, sitting on the camp’s front porch. “Not everybody gets to have the kind of end of life that they want,

so they’re very fortunate. I think all the children see that and she definitely sees that.”

White said the DeWaters family is a good model for others because they contacted a hospice agency as soon as there was a terminal diagnosis so they could

make their wishes clear and establish relationships with care providers.

They also were able to put aside common family differences so they could focus on caring for their mother. And they opened themselves up to the dying

process and the extraordinary gifts that it can bring. But every individual, every family, does it their own way.

“There’s no right way to do this,” White said. “You have to do it the way your family survives and exists. This family, they use a lot of humor and they’re

very open and they’re very loving, so that’s how we do it with them. Other families don’t do it that way. We try to normalize the process, because you know

what? Everybody’s going to die.”

White said she feels honored that hospice patients and their families let her into their lives. It’s an experience that helps her keep the rest of her life

in perspective and appreciate how fragile life is.

“This is a very vulnerable time, so to witness that and help people through that is really such a gift,” White said. “It’s really an honor for us.”

THE NEXT MORNING

Barbara DeWaters died just after 11 a.m. on Aug.13. The sunshine of the preceding day had given way to drizzling rain.

Cindy Higham had arrived early that morning to bathe her and change the sheets and her nightgown. It was her wish that she always be kept clean. Her

youngest daughter helped Higham to move her in the bed.

“She really didn’t wake up,” Jan DeWaters said. “It felt like she was already slipping away.”

The kids had been taking turns sitting at her side. Her oldest daughter was there when she passed.

“She breathed in and that was it,” Barbara Leighton said. “It was very quiet, very peaceful.”

The family called the funeral home to let them know she had died but asked them to pick her up the next morning.

“Cindy told us, ‘Don’t let anybody rush you through anything. It’s completely up to you how things go.’ So we decided to keep her with us for a while,” Jan

DeWaters said.

For the rest of the day, Barbara DeWaters’ kids took turns sitting with her, talking with one another, crying. Her oldest daughter went for a walk on the beach.

“I wanted to be alone for a while,” said Barbara Leighton.

By evening it was pouring rain, a fierce storm that flooded streets and left cars stranded across southern Maine. The power went out at the camp while Jere

DeWaters, the youngest son, was making spaghetti and meatballs, so he finished cooking them on the grill. By now they were drinking wine and telling

stories and relishing the shared time that their mother’s passing had given them.

“It took Mom to get us all back together in an unfortunate situation,” said Jere DeWaters, 63, a photography professor at the University of Maine at

Augusta who lives in Portland. “We never would have gotten back together and spent this concentrated time together without her.”

The next morning, the sun returned. When the undertaker arrived, Barbara DeWaters’ children wrapped her in a New England Patriots’ blanket – she was a big

fan – and tucked several goodbye notes inside. As they rolled her out to the hearse, they stopped briefly and tipped the gurney a little so she could face

the lake one last time. Jere DeWaters’ wife, Elise Scala, drizzled a little lake water on her forehead.

And then she was gone.

Earlier in the summer, Jere DeWaters had called attention to a clump of white birch trees in front of the camp. It had been there forever, taken for granted as many natural features are when they’re seen every day. But he noted now that the clump included one older trunk, clinging to the water’s edge, anchored by five younger trunks. The clump of trees came to symbolize their family coming together to be with their mother as she passed.

“It was an amazing experience to get to know each other again and take care of Mom,” Rick DeWaters said. “Now, we’re talking about getting together next

year and doing things together that we never have before. She was an amazing woman. We were all good children.”

HOSPICE RESOURCES:

It can be hard to find up-to-date, comprehensive information about hospice providers in Maine, even on the state’s Department of Health and Human Services website:

- The DHHS Division of Licensing and Regulatory Services offers an online Licensed Provider Search that lists hospice agencies by name, county or town, but it was last updated in January. Here’s the Web link: https://gateway.maine.gov/dhhs-apps/aspen/

- The National Hospice Locator is a free, regularly updated, searchable website that offers some basic information about every known hospice provider in the United States. It is produced and maintained by Hospice Analytics, a nationally recognized hospice research and consulting firm. Here’s the Web link: www.hospiceanalytics.com/

- For a current list of state-licensed providers, to request copies of recent hospice survey reports or to file a complaint about a hospice provider, call the DHHS Division of Licensing and Regulatory Services at 800-791-4080 or 207-287-9300. Here’s the Web link: www.maine.gov/dhhs/dlrs/

- For help accessing hospice care or to file a complaint about a hospice provider, call the Maine Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program at 800-499-0229 or 207-621-1079. Here’s the Web link: www.maineombudsman.org/Hospice/index.php

- To report abuse by a hospice care provider, call the Adult Protective Services hot line at 800-624-8404. Here’s the Web link: www.maine.gov/dhhs/oads/aging/index.shtml

- For information about or help accessing hospice care, call the Maine Hospice Council & Center for End-of-Life Care at 207-626-0651 or 800-438-5963 Here’s the Web link: http://mainehospicecouncil.org/

PART VIII: DOUG JOHNSON & FLO RICH

The dating game (Vintage edition)

Across Maine and the nation, a higher percentage of people are embarking on their old age unmarried. But many, like Doug Johnson and Flo Rich of Harpswell, are taking a fresh look at love, and walking into the future together.

Part IX: Hospice

Red flags? Maine hospice measures fall below national averages

The risk of loving Medicare funding or certification helps to counter the potential for waste, fraud and abuse, officials say.

Further Discussion

Here at

PressHerald.com we value our readers and are committed to growing our community by encouraging you to add to the discussion.

To ensure conscientious dialogue we have implemented a strict no-bullying policy. To participate, you must follow our

Terms of Use.

Questions about the article? Add them below and we’ll try to answer them or do a follow-up post as soon as we can.

Technical problems? Email them to us with an exact description of the problem. Make sure to include:

- Type of computer or mobile device your are using

- Exact operating system and browser you are viewing the site on (TIP: You can easily determine your operating system here.)