DEMOGRAPHICS | July 21, 2013

The demographics of Maine

With an abundance of baby boomers and not enough babies, the state with the highest median age grapples with a reality that University of Southern Maine public policy expert Charles Colgan says paints a grim economic forecast.

I

t’s often been said that Maine is the oldest state in the nation. But how can that be true when other states have a higher percentage of senior citizens?

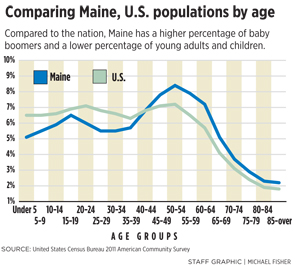

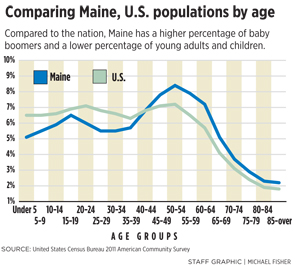

The answer is found in Maine’s demographic profile. We have a surplus of baby boomers and a shortage of young adults.

Maine’s age-distribution is “out of balance,” said Charles Colgan, professor of public policy and management at the University of Southern Maine’s Muskie School of Public Service.

“It’s not that we are disproportionately old,’ he said. “It’s that we are disproportionately not young.”

Maine’s oldest-in-the-nation status comes from its median age of 43.5 years, according to a 2012 estimate by the U.S. Census Bureau. New Hampshire and Vermont ranked second and third.

“Median” is a statistical term that identifies the middle number of a list of numbers. That means that half of Maine’s population is older than 43.5 years, and half is younger.

No other state has a higher median age. Utah has the lowest at 29.9 years. The national average is 37.4 years.

Maine’s median age is high because only one other state (New Hampshire) has a higher percentage of people between the ages of 45 and 64 – roughly the baby-boom generation – and no other state has a lower percentage of people between the ages of 15 and 44, according to a 2012 Census estimate.

Moreover, Maine trails only Vermont in having the lowest percentage of people under age 18, However, when it comes to the percentage of the elderly – people over age 85 – Maine is 10th in the nation, behind Rhode Island, North Dakota, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Florida, Connecticut, South Dakota, Hawaii and Massachusetts.

Maine has 411,540 people between the ages of 45 and 65, but only 301,124 people between age 20 and 39.

Maine's dependency ratio

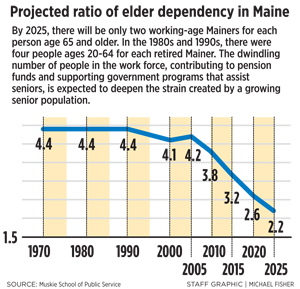

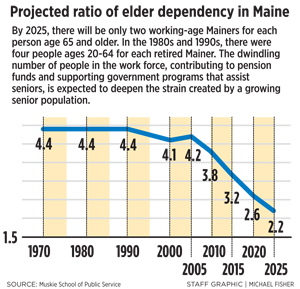

The "dependency ratio" refers to the number of working-age adults divided by the number of non-working dependents.

As Maine's retired population grows, this ratio is expected to shrink dramatically: a smaller proportion of taxpayers

will need to cover increased health care costs, and comparatively fewer

working-age adults will be available to work as caregivers.

Compare the state's past and projected age profile:

2000

2012

2027

Sources: US Census Bureau and Fralich, J. et al., Older Adults and Adults with Disabilities: Population and Service Use Trends in

Maine, 2012 Edition (Chartbook). Portland, ME: University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public

Service; 2012, based on data from 2012 New England State Profile: State and County Projections to 2040,

© 2011 Woods and Poole Economics, Inc. Woods & Poole does not guarantee the accuracy of this data.

The use of this data and the conclusions drawn from it are solely the responsibility of the Muskie School.

So over the next two decades, as the baby-boom generation leaves the work force and retires, the number of available workers contributing to the Maine economy will decline, said Colgan, who has studied Maine’s demographic data for more than 30 years.

For individuals, the labor shortage will be good news because employers will be forced to increase wages, he said. For companies, however, higher labor costs will make it harder for them to compete with firms outside the state and grow.

The only solution is to bring more people to Maine, he said.

“If they don’t show up, Maine’s economy starts shrinking,” he said. “We simply don’t have the people to do that work.”

There has been a lot of discussion among politicians lately about Maine’s “skills gap,” the perceived mismatch between the skills needed by employers and the skills being taught in schools and colleges.

But just revamping the skills of the current population is not enough, said state economist Amanda Rector.

“There’s a people gap,” she said. “There are not enough warm bodies to go around.”

Rector is projecting that Maine’s population by 2030 will be about the same as it is today. However, it will be significantly older because the youngest baby boomers by then will all be older than 65.

The number of children in Maine has been on the decline for years. Since 1975 – the peak year for school enrollment in Maine – the number of children in school has fallen from 253,000 to 186,000, a decline of 26 percent.

Don’t blame Maine mothers, though. The state’s birth rate – 53.6 births annually per 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 44 – is about average for non-Hispanic whites nationally.

Minorities have significantly higher birth rates. Because Maine’s population is among the whitest in the nation, the state has among the lowest birth rates in the nation, behind only New Hampshire and Vermont, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Also, as the number of Maine women of childbearing age has been declining for the past three decades, so has the number of babies being born.

In 2011, for the first time in at least 70 years, more people died in Maine than were born here, according to data from the state’s Office of Vital Records. The same held true for 2012.

The trend has political implications that are just starting to emerge, Colgan said. As the state struggles to provide for the needs of a growing number of senior citizens in the face of a shrinking economy and tax base, pressure will grow to cut spending on schools at the local and state level, he said.

The constituency for schools – families with children – will find themselves outnumbered and out-voted in many cities and towns, particularly in rural parts being abandoned by young families due to the lack of jobs.

“There will be a lot of horrible fights about school budgets,” he said. “The worst fights will be in suburban towns where there will be a mix of young families and the elderly. In much of rural Maine, there won’t be any young families to fight with.”

Laurette Lauze

The crisis in housing

As Laurette Lauze of Lewiston can attest, a backlog of projects and increasing demand mean the already lengthy waiting lists for subsidized living arrangements for seniors will only grow longer.

Demographics

The big picture

As life expectancy climbs and birth rates fall, aging populations the world over will present cultural and economic hurdles on an unimaginable scale.

Further Discussion

Here at

PressHerald.com we value our readers and are committed to growing our community by encouraging you to add to the discussion.

To ensure conscientious dialogue we have implemented a strict no-bullying policy. To participate, you must follow our

Terms of Use.

Questions about the article? Add them below and we’ll try to answer them or do a follow-up post as soon as we can.

Technical problems? Email them to us with an exact description of the problem. Make sure to include:

- Type of computer or mobile device your are using

- Exact operating system and browser you are viewing the site on (TIP: You can easily determine your operating system here.)