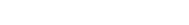

Larry Gillert is well aware of the good and the bad that he has done in this life.

A man of deep faith, he also has a pretty good idea of what to expect in the next one.

He talked about all of it, including what he’s done to make amends over the years, with a chaplain provided under his Medicare hospice benefit.

“I’ve probably done more than enough, really,” said Gillert, 65, sitting on the sofa in his modest but tidy Portland apartment.

“I just wanted to go over basic things,” Gillert continued. “I think I wanted him to reassure me there was a heaven. I just needed someone else to tell me

that, really, ‘cause I believe there is, but I just needed confirmation on that.”

In the final stages of liver cancer, Gillert has met several times with the Rev. David Heald, a priest at St. Nicholas Episcopal Church in Scarborough who

works for Hospice of Southern Maine.

Chaplain services are among the more humane benefits offered by any government-funded program. Hospice agencies must offer patients the opportunity to

speak with a chaplain or a representative of their faith. The service is free to patients, covered by the $155 per day that hospice agencies receive to

provide a patient with end-of-life care.

Some hospice patients say “absolutely not,” Heald said, because they don’t want to be “evangelized.” But that’s not how it works.

“My role is to respond to the patient wherever they are in their spiritual journey,” Heald said, adding that he basically affirms, clarifies and responds

to any ideas, questions or fears that a patient might have.

And his talks with Larry Gillert?

“Larry’s done a lot of spiritual work already,” Heald said. “He’s diligent about preparing for death. He’s done it in a wide-awake, grounded way that’s

exceptional. There’s little for me to do other than to listen and affirm his process.”

Heald also tries to bring family members and friends of hospice patients together for “prayerful” encounters, which he describes as quiet times that allow

for unconditional love and acceptance. It can be especially effective for families who are busy or dysfunctional, Heald said, giving them a reason to come

together, focus on the person who is dying and go to a deeper place.

“Amazing things can happen in a prayerful space,” Heald said. “I can adapt that to the person’s needs so it doesn’t have to be a prayer from a book and

there isn’t a lot of God or Jesus talk. A few times a patient has died when the family is praying around the bed.”

Heald said he has encountered a spectrum of believers during his eight years in hospice care, from patients who have minimal spiritual awareness or are

“unchurched” to those who are devoutly religious and ask him to contract a clergyman of their faith.

But being faithful doesn’t necessarily mean people are any less afraid of death.

in their words

an interview with Larry Gillert

“You can have a devout Roman Catholic who’s still scared of dying,” Heald said. “People come to a place of deeper acceptance, but it doesn’t necessarily

rule out those moments of fear and doubt. So you affirm both places. It’s all OK. It’s all good. Because it’s a rare person who comes to the end without

some disquiet or anxiety.”

Larry Gillert has those moments, when he has trouble sleeping, around 2 or 3 a.m.

“For two minutes or whatever, I’ll just feel this fear in me,” Gillert says. “Suppose I’m wrong and it’s just nothing. A deep sleep. That would be

disappointing to me now. In my heart I don’t believe it will be like that. I believe it’s gotta be good.”

A New York native who later lived in Florida, Gillert is a former social worker and building contractor who moved to Maine 14 years ago to help care for

his ailing parents.

Looking back, he’s proud of his children and grandchildren and the work he did as a social worker in New York City. He’s also proud of the time he helped

to save a drunken college kid who was drowning in the crashing waves when Hurricane Andrew hit Boynton Beach, Florida, in 1992. Gillert’s friends saw him

on CNN when the national network picked up news footage of the rescue.

But Gillert had a tough time as a young man. Drugs took hold in the 1960s and it was the 1980s before he was able to pry himself free.

“I gotta talk to the chaplain about a couple of things,” he said. “I’ve forgiven myself a long time ago. I’ve got through this life without killing anyone

or taking all their money or anything like that. I’ve made amends ever since I turned my life around.”

Heaven? That’s less certain.

“I don’t really know. No one knows,” Gillert said. “It’s gotta be someplace nice. I believe in Jesus and I believe in just about everything in the Bible.

I’m really hoping it’s a forgiving god and a loving god.”

He hopes to see people he knew in this life who’ve gone before him.

“But I only want to see the people I like,” Gillert said. “I don’t want to see people I don’t like.”

He laughs.

“Put it this way: I’m hoping it’ll surprise me and be one beautiful day when I open the gates or they open the gates for me,” Gillert said. “I’m really

counting on that.”

Larry Gillert died Thursday, Oct. 23, 2014.

Part IX: Hospice

Incarcerated, and taking care of their own

Behind bars, the growing need for hospice care among aging prisoners is satisfied in part by specially trained fellow inmates doing ‘the most important work’ of their lives.

Further Discussion

Here at

PressHerald.com we value our readers and are committed to growing our community by encouraging you to add to the discussion.

To ensure conscientious dialogue we have implemented a strict no-bullying policy. To participate, you must follow our

Terms of Use.

Questions about the article? Add them below and we’ll try to answer them or do a follow-up post as soon as we can.

Technical problems? Email them to us with an exact description of the problem. Make sure to include:

- Type of computer or mobile device your are using

- Exact operating system and browser you are viewing the site on (TIP: You can easily determine your operating system here.)