Portland’s Plea is Answered

Before the smoldering ruins of Portland’s Great Fire had cooled, city leaders were calling on communities near and far to send food, shelter and money to rebuild.

With City Hall destroyed, leaders used the nearby Mechanics Hall to coordinate the relief effort, as well as manage other city affairs.

Concerned that the fire would rekindle itself and destroy what was left of the city, Portland Mayor Augustus E. Stevens printed handbills and immediately distributed them to residents. There were also reports of looting taking place.

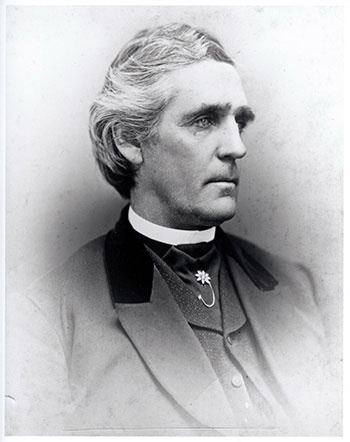

Augustus Stevens, Portland mayor during the Great Fire of 1866. Photo courtesy of Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

“LOOK TO THE FIRE!” the leaflet screamed. “I urge upon the citizens of Portland who still have Dwellings or Stores standing, the importance of keeping WATCH TO-NIGHT. And also of having BUCKETS and TUBS of WATER at hand to keep their roofs well wet, as a change of the wind would re-kindle the fire and destroy the western portion of the city.”

By July 7, the city had established a committee to oversee relief efforts. Mayor Stevens telegraphed an appeal for financial assistance to newspapers throughout the U.S. It was entitled, “Appeal from Portland.”

“The inhabitants of Portland, smitten by a more terrible disaster than has ever fallen upon any American town, of like population, are constrained to appeal to their countrymen, whom god hath prospered, to help them in this great calamity,” the appeal began. “We hasten to answer, respectfully but imploringly, that we need contributions of money, in large amount, and as soon as may be.”

As news of the disaster spread, the city received telegrams from people inquiring about loved ones.

Katie Robertson asked about John Bush – “the blind man and his wife” – who had not responded to two letters. And Oliver Jackson, of Philadelphia, asked about his mother, Rebecca, who lived at 19 Green St. and at Mrs. Wobert’s boarding house on Pearl Street.

U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton immediately telegraphed Mayor Stevens, offering whatever assistance was needed. About 1,500 tents used during the Civil War were sent from nearby Fort Preble and Fort Scammel.

Mayor Stevens’ appeal for financial assistance was telegraphed to newspapers throughout the country. Courtesy of Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Soldiers were deployed to stop the widespread looting taking place. (One news account related a story about a stolen piano being recovered in Cape Elizabeth.) Two special police forces – one made up of marines and another of regular citizens – along with armed residents, were successful in turning back opportunistic thieves, whom Stevens described as “a multitude of rough and disparate characters” from larger cities.

“Those who had come to prey upon us left and good order and quiet were soon restored,” Stevens said in his first annual report to the Portland Board of Alderman after the fire.

Food donated by surrounding communities was distributed at the old City Hall in Monument Square and at the Ward Room on Munjoy Hill. By July 7, more than 6,000 rations of food and 600 gallons of coffee had been given out in Monument Square alone, according to the July 10 Easter Argus. On Sunday, an additional 2,950 rations were distributed.

The Irish living on Munjoy Hill opened their doors to their fellow countrymen. The Eastern Argus reported July 10 that homes were “packed as full as beehives.”

The city promptly received additional supplies from military depots in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, including: 4,000 woolen blankets, 3,036 bed sacks, 1,500 camp kettles, 565 tin cups, 24 spoons, 891 mess pans, 1,696 pairs of drawers, 1,029 shirts, 500 pairs of shoes and 500 stockings.

A wide variety of donations began to flow in.

Bangor Mayor Albert G. Wakefield relayed $50 from the Morris Brothers and Trowbridge Minstrels, who were scheduled to perform July 4. The mayor of Belfast returned a box of goods that had been stolen during the fire. And Boston’s clerk of street lamps offered to relight the city streets, providing oil and burners for free. Raoland Johnson of New York sent oolong tea for “destitute widows.”

The city received money in amounts small and large.

Boston reportedly contributed $25,000, or more than $600,000 today.

Edwin Colby, a 12-year-old schoolboy from Lowell, sent the $12 he raised in a day. A group of New Jersey girls, ages 8-13, sent $100 they raised through a small fair. O.L. Perry donated $1 that he had earned shoveling snow.

Hartford, Conn., sent the city $2,245 from its residents, but Mayor Chas R. Chapman couldn’t help but point out that his city was also suffering, since its economy heavily relied on the insurance companies that were inundated with claims.

Local fundraising efforts also took place. Amateur thespians staged two comedies on July 20 to benefit the Portland sufferers: “Married Life” and “Who Stole the Pocket Book.” Admission was 50 cents, or more than $12 today.

By August, the city had received $269,000, or $6.5 million in today’s currency, from people and communities as far away as Cuba.

By October, local author John Neal, who documented the fire and its aftermath, wrote that figure had grown to $500,000, or roughly $12 million in today’s dollars.

The final distribution from the relief fund was made on Sept. 16, 1867.

The Great Fire of 1866

The Night Portland Burned

A firecracker and a pile of wood shavings turn a day of celebration into a “frightful calamity.”

MorePortland's Plea is Answered

Before the smoldering ruins of Portland’s Great Fire had cooled, city leaders were calling on communities near and far to send food, shelter and money to rebuild.

More

Tell your friends