City Rises From the Ashes

One-third of the city was left in ruins, piles of smoldering rubble surrounding brick chimneys and walls that wouldn’t burn and refused to fall. But, what took less than a day to destroy would also be rebuilt surprisingly quickly.

It would take only a few years to rebuild Portland’s commercial center, with the help of architects and laborers who descended on the city from as far away as Boston. Photographers also arrived from afar to document the war-like destruction, and the recovery.

Portlanders survey the destruction. Photo courtesy Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Photos taken between July 12 and 14 by John P. Soule of Boston show well-dressed men in suits, suspenders and caps standing near neatly stacked mounds of brick, salvaged from the ruins and reused in the new buildings.

“As remarkable as the tale of the fire is, the story of the recovery is even more remarkable,” local historian Herb Adams said. “All of these spectacular brick and finished stone and iron-wrought fronts of Exchange, and parts of Commercial Street and Middle Street, all went up in the short months right after the fire.”

Wooden residential buildings disappeared from the downtown and a true commercial center, consisting of three- to five-story buildings began to dominate what is today’s Old Port. Generally, Victorian styles of architecture – Italianate, Queen Anne and Gothic styles – replaced the old Federal-style buildings that were reduced to ashes, especially around Exchange, Market and Middle streets.

“That was one of the great positive byproducts of the fire,” said State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., noting that city officials banned the construction of wood-framed buildings downtown after the fire. “Portland got an entirely new commercial district, which for the late 1860s and early 1870s when it was built, was state of the art.”

Workers sort through bricks on Middle Street. Photo by J.P. Soule. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

More modest wooden homes began to rise on East End.

Much of Exchange Street was rebuilt within a year, including Thomas Block at 22-26 Exchange St., Merchant Bank at 34 Exchange St., Bailey and Noyes Block at 58 Exchange St., and Portland Savings Bank Block at 81-89 Exchange St.

Woodman Block, a massive four-story brick building occupying the northeastern corner of Market and Middle streets, was completed in 1867. City Hall, which was gutted by flames, was also rebuilt. A new North School on Congress Street was built shortly thereafter.

The Falmouth Hotel, built by Brown the following year at 212 Middle St., added to the excitement of Portland’s renewal. The six-story building, which cost $300,000 to build, or $7.3 million in today’s dollars, had 200 rooms, with black walnut interior designs and state-of-the-art billiards tables. A story about the hotel opening in the June 29, 1868, Eastern Argus said, “it has justly been termed one of the finest hotels this side of the Pacific shores and a boon.”

The new Custom House on Fore Street was also completed a few years later.

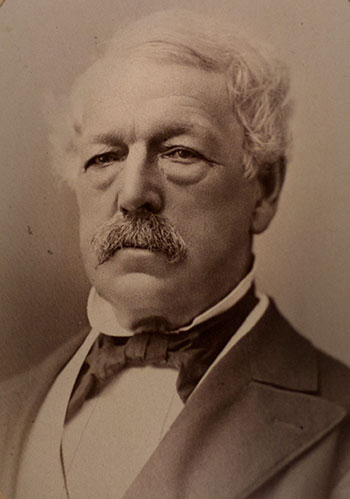

John Bundy Brown immediately began rebuilding his Portland businesses. Photo courtesy of Collections of Maine Historical Society.

In his first annual report to the Portland Board of Alderman following the fire, Mayor Augustus E. Stevens said the industriousness of Portland’s capitalists inspired others to get to work, rather than wallowing in gloom and despair.

“This stimulated others and ere a week had passed, (and) our streets were the scene of intense activity and life,” Stevens wrote. “Mechanics and artizens came in from every quarter; building materials and labor off all kinds were in demand, and before the smoke from the ruins had fairly cleared away, new stores and dwellings, as if by magic, were rising in every direction.”

But it was more than the entrepreneurial spirit that inspired the capitalists – the streets were crowded with a restless workforce of newly unemployed laborers.

The July 10 edition of the Eastern Argus contained this excerpt from the Boston Journal: “Hungry mouths and shelterless forms are appealing to too many. Work they must have, and if it is not supplied immediately in Portland, they will go elsewhere to the lasting injury of this city.”

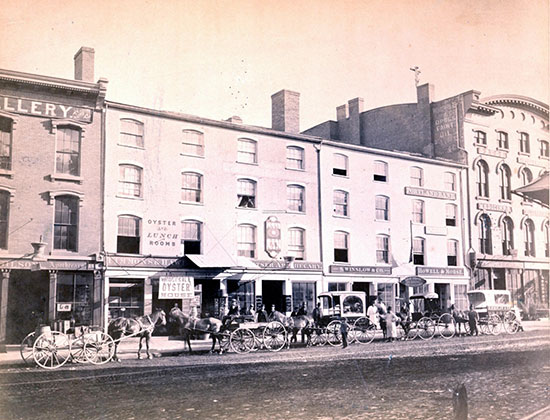

Businesses line Market Square – now Monument Square – around 1870. Photo courtesy of Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

A writer for the July 28, 1866 edition of Harper’s Weekly also observed the early determination of area residents to remake their city.

“The activity of the Portlanders impresses the mind... On many lots workmen are picking out the unbroken brick, chipping the calcined mortar from them and piling them up for use. Carts and wagons are treading their embarrassed way through the choked streets, carrying off rubbish, or bringing on materials for new erections.”

Favorable weather allowed construction to continue well into the winter, according to author John Neal, who wrote detailed accounts of the fire and notes about the city’s rebuilding efforts. The day after Christmas of 1866, he noted that workers were busy putting on roofs “by the score.”

Not even waist-deep snow at the turn of the year could freeze Portland’s progress. On Jan. 27, 1867, Neal wrote, “Our people are swarming to their work, early and late; the city is going up silently through the deep snow, block after block, and street after street.”

By May 23, 1867, he reported that all of the buildings that had begun construction had been finished “with improvements 100 years in advance of what they were before.” By that fall, enough buildings had been erected that one had to walk about the new street grid to see the progress.

Many of the brick buildings along Exchange Street were built within a year of the fire. Staff photo by John Richardson.

By Jan. 1, 1868, Neal declared: “Another year! Portland is now rebuilt and greatly enlarged and beautified.”

It was a speedy outcome few could have imagined as the sun rose on July 5, revealing a city in ruins.

“The city has been destroyed four times in its history,” said Shettleworth – twice during the French and Indian War and once by a bombardment by fleet of British Naval vessels in 1775. “After all, what is its motto? Resurgam: I shall rise again.”

The Great Fire of 1866

The Night Portland Burned

A firecracker and a pile of wood shavings turn a day of celebration into a “frightful calamity.”

MorePortland's Plea is Answered

Before the smoldering ruins of Portland’s Great Fire had cooled, city leaders were calling on communities near and far to send food, shelter and money to rebuild.

More

Tell your friends