Fire's Lasting Impact Both National and Local

Portland’s Great Fire of 1866 prompted national insurance reforms that are still in place, and it forever changed Maine’s largest city.

“The city that we live in today is the city that came out of the Great Fire,” said Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., Maine’s state historian.

The largest urban fire in U.S. history at the time, Portland’s conflagration galvanized the insurance industry to come up with uniform rates and standards for providing fire insurance. It led to the creation of the National Board of Fire Underwriters, which is now known as the American Insurance Association. Today, home insurance rates are determined, in part, by the amount of fire protection provided by the community.

The U.S. insurance industry was already dealing with significant fire losses before Portland’s historic fire.

In 1866, there were an average of 1,500 fires a day in the United States, with daily losses of $600,000, more than $14.4 million in today’s currency, according to “The History of the National Board of Fire Underwriters: Fifty Years of a Civilizing Force,” published in 1916. Fire losses had been increasing since the Civil War, but an increase in competition among insurance companies kept rates artificially low. A new system was needed to ensure that insurance companies remain solvent.

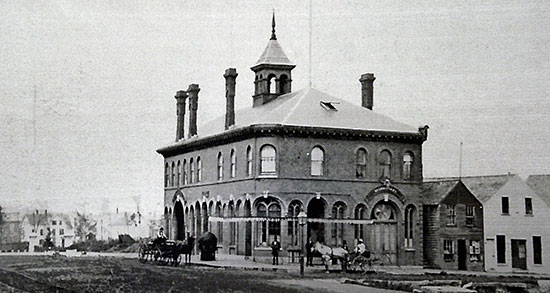

One of the new fire stations built after the Great Fire, this one is at the site of the current Central Station. Photo courtesy of Portland Fire Museum.

Chas R. Chapman, mayor of Hartford, Connecticut, noted the impact Portland’s fire had on his city’s insurance industry, which at the time rivaled that of New York City.

“Much sympathy is felt and expressed here for those who have met with such a great calamity,” Chapman wrote in an 1866 letter to Portland. “Owing to the fact of many Insurance Companies being located here we have ourselves suffered much pecuniarily from the fire in your city, but it has been a pecuniary loss only, it has not involved as with you the breaking up of business and the destruction of happy homes. Trusting that Portland will soon recover from her present prostration, and be in the future as prosperous and happy as she was in the past.”

Shortly before the fire, the New York Board of Fire Insurance Companies voted to appoint a committee to consult with representatives from other states to set rates. But it wasn’t until July 7 – only two days after Portland’s fire burned itself out – that it took emergency action to establish a national board to come up with national standards and rates.

“Incidentally, the $10 million Portland conflagration occurred dramatically at that very moment and stimulated eagerness,” according to the underwriters history book. “Many felt it to be almost a matter of life or death that they should ‘do something’ without delay.”

Back in Portland, the legacy of the fire is virtually everywhere.

Sebago Lake water supply: One of the reasons the fire was so destructive was because a drought had left city reservoirs and wells dry. And, because the fire started at low tide, drawing water from Fore River was not an option. As a direct result of the fire, the Portland Water Co. was chartered in 1866 to draw water from Long Creek in Cape Elizabeth. Its charter was amended the following year to make Sebago Lake the city’s water source. The lake is 260 feet above sea level, which provides ample water pressure to fight fires. On May 4, 1867, construction crews began laying 17 miles of pipe from the lake to Portland. The project was finished on July 4, 1870. Sebago Lake remains the city’s water source to this day, but it’s operated by the Portland Water District.

“They were never again going to be without a water supply,” Shettleworth said.

Lincoln Park was created at the site of a destroyed neighborhood to serve as a fire break. Derek Davis/Staff Photographer.

Lincoln Park: The 2.5 acres of land bounded by Congress, Franklin, Federal and Pearl streets was a residential neighborhood before the fire consumed it on its way across the peninsula before reaching open land below the Portland observatory. The city purchased the block on Aug. 6 of that year for $83,000, or more than $2 million in today’s dollars, to create a park that would also double as a firebreak to prevent any future fires from destroying both sides of the city. It was originally named Phoenix Square, but was later renamed to honor former President Abraham Lincoln in 1867.

Bayside begins to emerge: In 1866, Portland’s Back Cove reached farther into downtown, touching Somerset Street and nearly reaching Fox Street. After the fire, much of the debris that was cleared from the city center was dumped into Back Cove, which began the process of creating much of the East and West Bayside neighborhoods.

The Old Port: Much of Portland’s Old Port area along Exchange, Fore and Middle Streets is made up buildings that were constructed immediately after the fire. The area was reconstructed primarily as a commercial center. Many of the bricks used in the buildings were pulled from the rubble of the fire.

City leaders banned the construction of wooden buildings downtown to prevent re-creating the tinderbox-like conditions that existed before the fire. The order, enacted July 12, 1866, applied to the area bounded by Congress, Pearl, Middle, Franklin, Commercial and Center streets. It also ordered the removal of any buildings that violated the rule. Middle Street, which at the time had a gradual bend to it before the fire, was straightened out during the rebuilding. It was one of many roads that were extended, widened or realigned to create a street grid that largely exists to this day.

East and West Ends: While the Old Port was rebuilt as a commercial district, residential development was generally directed to the ends of the peninsula. Portland’s wealthier residents purchased land to the west and built the mansions that have since lent a gentrified air to the West End. The city’s less affluent settled in the more modest wooden homes on the East End, a section of the city that would be home to waves of immigrants and working-class Portlanders.

Investments in Fire Department: After the fire, Portland’s fire department was allocated 11 horses and six drivers so that it no longer had to rely on horses from public works to pull their steam engines. Additionally, the city purchased a new steam engine and a hook-and-ladder, as well as 3,250 feet of new leather hose and 400 feet of rubber hose.

A contract for a $5,300 telegraph machine was signed. A year later, the fire chief would report to the council that the response times had been cut in half, from as long as 30 minutes to 15 minutes or less. Three fires stations were destroyed by the fire, but a new two-story station was built at Congress and Market streets – where today’s Central station now stands.

“It would seem that with the sad experience of the last year we should not again need to be reminded of the importance of leaving nothing undone that can add to the efficiency of the fire department,” Mayor Augustus E. Stevens said in his first annual report to Portland’s Board of Aldermen after the fire.

To this day, Portland’s Fire Department is among the most advanced and highly staffed among cities of its size. It also enjoys a relatively low fire risk rating, due to the placement of its fire stations.

Legacy Seared into History

150 Years Later, Death Toll Revealed

One of the disaster’s lingering mysteries is laid to rest when the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram examines Portland’s original death records.

MoreFire's Lasting Impact Both National and Local

The Great Fire leads to national standards for assessing fire risk, and it forges the city that survives to this day.

More

Tell your friends