A Place in the History of Great Fires

The burning of Portland is part of a long history of Great Fires around the world.

Portland’s Great Fire of 1866 was the worst urban fire in the history of the United States at the time. Within a decade, Chicago and Boston would have their own great fires and suffer even more destruction. Here is a look at other Great Fires in history.

64 AD – Burning of Rome: Emperor Nero was blamed for starting the six-day blaze, though a historian later claimed that the brutal dictator was out of town at the time. Started July 18 in shops near the Circus Maximus, fire destroyed or damaged about half of the city. It was rumored that Nero watched from his palace on Palatine Hill and played his lyre, giving rise to the saying, “Nero fiddled while Rome burned.” To satisfy his critics, Nero executed hundreds of Christians for alleged arson, crucifying or burning some and feeding others to lions during arena spectacles.

A painting by an unknown artist shows the Great Fire of London in 1666.

1666 – Great Fire of London: It started after midnight May 2 on Pudding Lane, near London Bridge, in a bakery that served King Charles II. London’s mostly wooden buildings were bone dry amid a lengthy drought, so the fire spread quickly, destroying about 80 percent of the city. Over the next three days, it wiped out 13,200 houses and 89 churches, including Old St. Paul’s Church. It also killed as many as 16 people and left 100,000 to 200,000 people homeless. On a positive note, it also killed many rats and ostensibly ended London’s last major outbreak of the bubonic plague.

1812 – Burning of Moscow: Three-quarters of the city was destroyed by fires set by Russian soldiers in retreat as Napoleon’s Grande Armée of 500,000 troops invaded the capital on Sept. 14. Though most of the city’s 270,000 inhabitants had fled, the four-day fire killed about 12,000 people and destroyed more than 14,700 buildings. Napoleon occupied the burned-out city through October, hoping Czar Alexander I would surrender, then withdrew his starving army in November, marching home through winter snows with fewer than 100,000 troops.

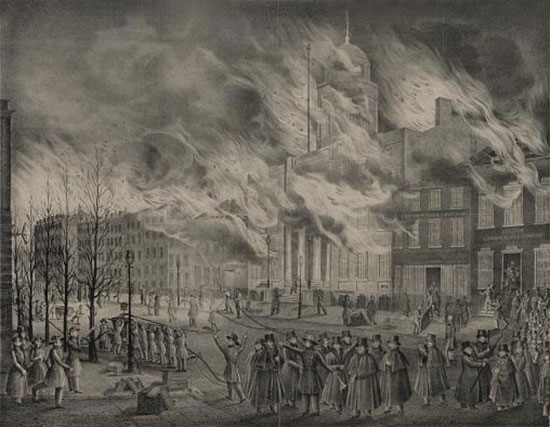

This print in the Library of Congress shows the Great Fire in New York on Dec. 16, 1835.

1835 – Great Fire of New York: It started the evening of Dec. 16 in Lower Manhattan, where a gas line burst and was ignited by a coal stove. Gale-force winds spread the blaze across 17 blocks, destroying more than 500 buildings and killing two people in 15 hours. Firefighters were hobbled because subzero temperatures had frozen water sources, including the nearby East and Hudson rivers. The flames melted iron shutters and copper roofs on newer buildings that were thought to be fireproof. Property damage was estimated at $20 million (at least $486 million today).

1845 – Great New York City Fire: It broke out July 19 in a whale-oil and candle factory, destroying 345 buildings in Lower Manhattan and killing 30 people, including four firefighters. The fire accelerated when it reached a large warehouse containing saltpeter, a component of gunpowder, which exploded and flattened several buildings. Property damage was at least $10 million (about $243 million today), but the limits of the fire demonstrated the value of building codes that required stone and brick construction following the 1835 fire.

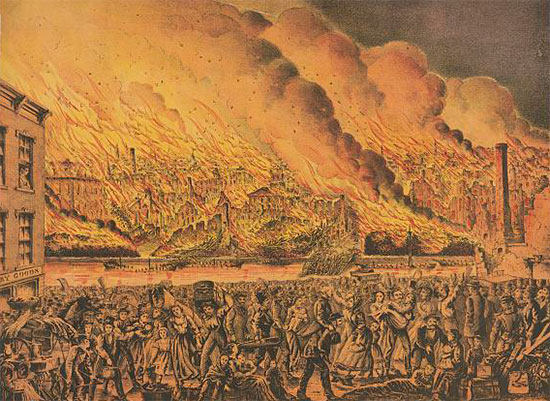

This lithograph in the Library of Congress shows the Great Fire at Chicago Oct. 9, 1871, five years after Portland burned.

1871 – Great Chicago Fire: The blaze started Oct. 8 in or near a barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary, possibly when Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern. Following a summer drought and fanned by strong winds, the fire burned through the city’s wooden houses, streets and sidewalks for more than two days. It killed as many as 300 people, destroyed 17,500 buildings and left one-third of the city’s 300,000 residents homeless. Property damage was estimated at $200 million (about $5 billion today).

This lithograph in the Library of Congress shows Boston’s Great Fire on Nov. 9-10, 1872.

1872 – Great Boston Fire: Originating in a warehouse on Summer Street, the Nov. 9 fire destroyed 776 structures and killed at least 30 people in just 12 hours. The flames spread quickly through narrow streets lined with both residential and industrial buildings made of wood. Property damage was estimated at more than $70 million ($1.7 billion today). In the wake of the fire, the city improved fire fighting and construction standards and built its financial district in the neighborhood that was destroyed.

1904 – Baltimore Conflagration: Started Feb. 7 in the John Hurst Building, the fire burned for 30 hours through the city’s business and retail districts. It destroyed 1,500 buildings, left 35,000 people unemployed and caused more than $150 million in damages (about $3.6 billion today). Despite relatively modern firefighting equipment, the blaze spread because crews from other cities couldn’t hook their hoses to Baltimore’s hydrants. The experience eventually led to a national standard, known as the Baltimore standard, for hydrant size and hose couplings.

1906 – San Francisco Earthquake & Fire: One of the most significant earthquakes of all time, the April 18 upheaval of the San Andreas Fault was felt from Los Angeles to Oregon and into central Nevada. It ruptured the city’s gas and water lines, leaving the fire department without the means to fight the resulting blaze that consumed the city for several days. In total, about 3,000 people died, 28,000 buildings were destroyed and as many as 300,000 residents were left homeless. Property damage was estimated at more than $400 million (about $10 billion today).

1911 – Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire: One of the deadliest industrial disasters in U.S. history, the March 25 fire in a Greenwich Village blouse factory killed 143 garment workers, most of them young immigrant women in their teens and 20s. Located on the eighth through 10th floors, the factory’s doors were locked to prevent unauthorized breaks and employee theft. Workers suffocated, fell or jumped to their deaths. The tragedy led labor unions to fight for and win more humane working conditions in so-called sweatshops.

1933 – Great Ellsworth Fire: On May 7, an arsonist set fire to the Old Bijou Theater Building, triggering a conflagration that destroyed most of the downtown business district and residences south of Main Street. At least 14 towns sent firefighters to help battle the blaze for several hours. They used dynamite to create a fire break, but still it spread through 150 buildings, and airborne debris set fires up to two miles away. Damage was estimated at $1.2 million ($22 million today). Charged with the starting the fire was Norman Moore, a dishwasher at a local restaurant, who was found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to the psychiatric hospital in Bangor, according The Ellsworth American.

1933 – Great Auburn Fire: The Depression-era blaze started May 15 at Pontbriand’s Garage on Mill Street, in a densely populated neighborhood of wooden tenements. Pushed by high winds, it destroyed 248 buildings within five hours, including two schools, and left more than 2,000 people homeless, many of them recent immigrants. Fire departments from 12 communities helped fight the flames and four national guard companies patrolled the area afterward. Property damage was estimated at $2 million ($37 million today). The rebuilt area is known as New Auburn.

Legacy Seared into History

150 Years Later, Death Toll Revealed

One of the disaster’s lingering mysteries is laid to rest when the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram examines Portland’s original death records.

MoreFire's Lasting Impact Both National and Local

The Great Fire leads to national standards for assessing fire risk, and it forges the city that survives to this day.

More

Tell your friends