The Night Portland Burned

John Marshall Brown, an heir to one of the largest fortunes in Maine and one of the so-called “Princes of Portland,” was enjoying a picnic with friends on a sunny July afternoon near the ocean.

Other Portlanders, from prominent authors John Neal and William Willis to firemen Frank Merrill and Alfred Wiggin, were going about their day as the city prepared for a giant celebration, the first Independence Day since the return of soldiers from the Civil War.

A parade was scheduled to wind its way through the dirt and cobblestone streets of the city. A circus was to take place on the Western Promenade. And the largest fireworks display in the state’s history was slated for dusk.

Meanwhile, Hannah Thurlow was inside her home on Fore Street, in what is now the city’s Old Port. At a frail 91 years old, Thurlow was no longer able to get out and stroll the streets of her hometown, a bustling seaport with tree-lined streets, densely packed wood-frame homes and a stately new City Hall.

Flames and smoke are shown rising over the Portland skyline on the evening of July 4, 1866. Image courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

The date, July 4, 1866, would indeed leave its mark on Portland history. But for far different reasons than anyone imagined.

“How little we expected the frightful calamity which was to come,” Brown would later write about that day.

The city of Portland was well-known for having endured destruction. It was practically flattened by a fleet of British naval vessels in 1775, prompting city leaders to adopt the phoenix – a mythical bird that rises from the ashes – as its symbol. In 1832, the city adopted the motto, “Resurgam,” which is Latin for “I shall rise again.”

On that morning in 1866, Portland was a premier city – a hub for trade and immigration. It was a full day closer to Europe by sea than any other U.S. port, its harbor rarely froze and it had railroad connections to Boston and Montreal.

Much like today, people were drawn to its economic opportunities and vitality. Brown’s family was a prominent example of the city’s prosperity, owning hundreds of acres of land in the West End and a lucrative sugar and molasses refinery next to both the waterfront and the railroad.

“All of these connections made Portland rich,” said Herb Adams, a local historian. “All of that came to a flaming halt in one night – July 4, 1866.”

A fire that started next to the harbor that afternoon would sweep across the peninsula, consuming one-third of the city before essentially burning itself out. Roughly 1,500 buildings, along with 58 city roads, were reduced to smoldering piles of rubble in roughly 15 hours, although some reports say it took several more hours to extinguish all of the flames. Losses exceeded $10 million, or well over $240 million in today’s currency.

More than 10,000 people were rendered homeless. There were conflicting and unconfirmed reports of deaths, including a report of a baby who was apparently thrown out of a burning building onto the street below. Perhaps because of the chaos at the time, however, there was no definitive accounting of those who perished.

The Portland Sugar House before the fire. Courtesy of Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

A Maine Sunday Telegram analysis of eyewitness reports and 150-year-old city death records revealed the identities of at least four people killed.

Those statements and records, along with newspaper reports, history books and interviews with historians and descendants of those who lived through the fire, shine a new light on a defining moment for the city and how it shaped the Portland that exists 150 years later.

Not only would The Great Fire of 1866 – or the Great Conflagration – forever change Portland, it also would send shockwaves through the country and beyond. The burning of Portland led to a new national system for assessing fire risk that still exists today.

“It is considered very quickly by everyone to be the worst urban fire up to that time in American history,” said State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr.

That Wednesday began with so much promise.

It was to be a celebration of both American independence and the return of soldiers from the Civil War. Mainers had made extraordinary sacrifices during the four-year conflict. The state contributed more than 70,000 troops, more soldiers per capita than any other state.

Although the war ended in the spring of 1865, few in the country were ready to celebrate Independence Day again until July 4, 1866.

“There was definitely a strong sense of rejoicing that (the war) was over and people were home,” Shettleworth said.

Special trains were running on the Grand Trunk railroad, bringing in people from Maine’s hinterlands for a day of activities, including a fireworks display billed as “the most brilliant ever exhibited in this state.”

Many of the city’s 30,000 residents, along with visitors, filled the narrow streets with horses and livestock ready to witness “The Fantastics” – “a grand display of oddities, caricatures and grotesque groupings.” Police, firemen and a military brass band were also slated to march and participate in ceremonies. Upper-class people wore their Sunday best – billowing dresses for the ladies, suits and derbies for the gentlemen. Commoners were likely wearing their everyday work clothes.

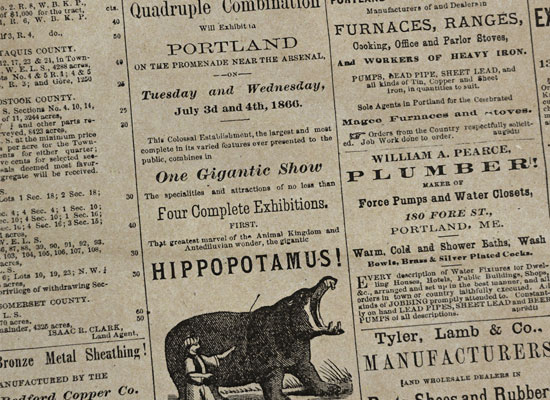

The Eastern Argus newspaper published a list of planned Independence Day events in Portland, which included fireworks, a hot air balloon and a giant hippopotamus called “the greatest marvel of the animal kingdom.” Courtesy of Earle G. Shettleworth Jr.

Early Maine efforts at prohibition had officially made Portland a dry city, with the lawful sale of alcohol restricted only to medicinal and manufacturing uses. But, there was no shortage of libations to go around, with black-market alcohol sales booming in the back rooms of Gorham’s Corner, an area just west of the Old Port where many Irish immigrants settled.

In Deering pasture, near today’s Parkside neighborhood, a crowd expected to see a hot air balloon rise at noon. On the Western Promenade, a “gigantic show,” featuring a hippopotamus, dubbed “the Behemoth of Holy Writ,” an Australian circus and four elephants trained to dance, play the organ and stand on their heads was kicking off its second day. Portland’s Eon baseball team was preparing to play its rival, the Lowell Nine of Boston. Horse races were planned, with purses approaching $250, or $6,000 in today’s currency.

The fireworks were scheduled to be ignited at dusk from the pasture, capping off a festive day.

But it wasn’t meant to be.

The hot air balloon was a bust, torn to shreds by the wind after it failed to take off. Portland’s baseball team got pummeled by Boston, 35-23.

And the only fireworks to go off were the incidental charges that detonated during the conflagration, which ironically began with a child playing with firecrackers on the waterfront.

A strong southwesterly wind was building in the late afternoon as two boys were getting into mischief near a boatyard on Commercial Street. One boy lit a firecracker and tossed it into a pile of wood shavings, igniting a small fire. It quickly spread to a nearby boat shed.

Shortly before 5 p.m., William Wilberforce Ruby was passing by the J.C. Deguio boat shop at Commercial and High streets. Ruby, a local merchant who would eventually become one of the first African-American officers in the Portland Fire Department, spotted the fire.

He sounded the alarm by shouting “Fire!” until word of a fire in District 8 reached a Park Street church, whose bell called all able-bodied men into service.

Eight bells. Then a pause. Then eight more, directing firemen to the fast-moving fire on the waterfront. The flames – stoked by the wind – quickly spread to a 2½-story building in the boat yard and was racing toward the Portland Sugar House and the N.P. Richardson stove foundry.

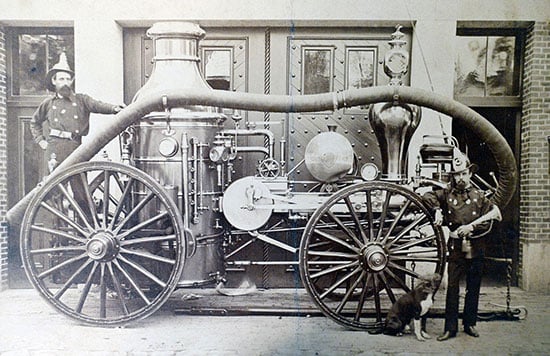

The holiday revelers did not seem alarmed as firefighters and horse-pulled steam engines rattled toward the waterfront , their carriage bells jingling with each gallop. That same day, two other fires caused by firecrackers had been easily extinguished with the fire department’s new steam engines, which pushed far more water than hand-pumps.

Author John Neal lived on State Street, where well-dressed church parishioners had gathered to listen to a Cape Elizabeth man describe the growing flames. The man was confident that the Brown family’s Portland Sugar House, believed to be virtually fireproof, would be lost.

Neal captured the complacency of the bourgeoisie in his “Account of the Great Conflagration in Portland, July 4th & 5th.”

“For the first half hour, indeed, so little concern was felt, that very few among the thirty-odd thousand inhabitants of our prosperous and beautiful city – one of the most beautiful and prosperous on the face of the earth – took trouble of ascertaining for themselves what the danger was, or which way the wind blew.”

Around the same time, John Marshall Brown was finishing his picnic with friends and his older brother, Philip, who owned a summer home on Glen Cove in Cape Elizabeth.

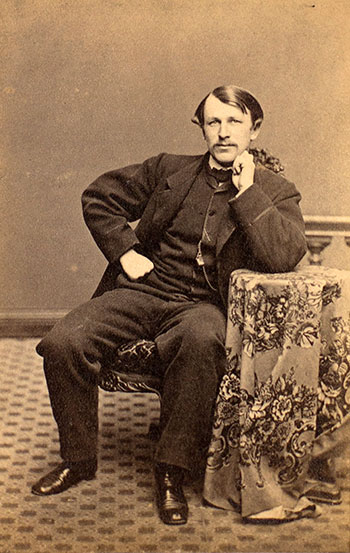

John Marshall Brown, shown here around 1868, tried to save his family’s sugar refinery. Photo courtesy of Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

John Marshall was readying the horses to return to his Vaughn Street estate, where he planned to put quill and ink to paper and compose a letter to his fiancée, Alida. A man on horseback swiftly approached, furiously shouting that the family’s sugar house was on fire.

The Portland Sugar House was owned by his 61-year-old father, John Bundy Brown, one of Maine’s wealthiest residents, who had made a fortune refining sugar from molasses shipped to the port from the West Indies. His business was located in an eight-story brick building that towered over Commercial Street and the Deguio boatyard, near what is now the foot of High Street.

John Marshall, a Civil War officer who fought at Gettysburg and was severely wounded in Petersburg, Virginia on June 12, 1864, sprung into action. When he arrived on horseback, two fire companies were on the scene, trying to douse the fast-moving fire with water. But it had been a hot, dry spring and summer and water was scarce.

Portland had not yet built a waterline from Sebago Lake. Firemen relied on reservoirs, wells and cisterns, which were quickly pumped dry by the efficient, coal-fired steam engines. The tide was out, so drawing water from the Fore River was impossible. Several fire hoses broke, further hindering efforts to stop the impending tragedy.

As the sugar supply burned, an ominous black cloud, pushed by a strong southwesterly wind, crawled over the city, a harbinger of the destruction to come.

Alida (Carroll) Brown, shown here around 1868, was engaged to John Marshall Brown when the fire struck, and his letter to her two days later provides a vivid account of the experience. Photo courtesy of Collections of the Maine Historical Society.

Realizing the building would be lost, Brown focused his efforts on rescuing important business papers, cash and other valuables in the office. For five hours, the 28-year-old “Prince of Portland” fought the flames shoulder-to-shoulder with volunteer firefighters.

“It seemed to me as if I had the strength of ten men,” Brown wrote in a letter two days later to Alida. “I worked in the hottest places, sometimes holding with the firemen the engine pipe, in the very face of the fire. Once I was nearly pushed off a high ladder & got badly bruised. Once I was obliged to drop down holding the ladder with my hands.”

“Of course I was drenched with water & thoroughly blackened with smoke. One of my eyes was burned also but thank Heaven I received no serious injuries,” he continued. “Alas it was to no purpose. The magnificent building was entirely consumed with its contents & the labor of 25 years seems blotted out altogether.”

As the sun set, the wind grew to a full gale, pushing the flames northeasterly across a mile-long swath of the city.

The fire quickly blossomed into a full-blown conflagration – a term that describes a fire that has spread to multiple structures. A conflagration burns with so much heat and with so much force, it makes its own wind, blowing burning splinters and cinders onto rooftops and igniting fires far into the distance. Some eyewitnesses described the fire as a hurricane, a tornado and a tempest.

Firefighters, primarily volunteers, were quickly overwhelmed. Chief Spencer Rodgers telegraphed Lewiston, Biddeford, Hallowell, Augusta, Saco, Bath, Brunswick, Gardiner and Boston for help. Crews fought throughout the night, as their own homes and families were threatened by the blaze.

“Here, the night of the Great Fire, you were fighting an advancing army,” said Adams, the historian. “Some of the Civil War soldiers found themselves reliving experiences of a little more than a year before. They’d make a stand and then be driven back by a remorseless old foe, make another stand and be driven back, make another stand and be driven back.”

Cumberland Steam Engine Co. 3 initially held back the flames at Danforth and Maple streets. But the fire quickly spread along York Street, consuming the jumbled assemblage of ramshackle wooden homes of the Irish at Gorham’s Corner. Livestock, including pigs and chickens, squealed and squawked in horror, wildly running through the streets.

People flee from the flames in painting by George Frederick Morse. Photo by Derek Davis/Staff Photographer. Courtesy of collections of Maine Memory Network.

“In Cross Street we saw a huge hog, almost as big as the hippopotamus exhibited at the circus, lying panting against the side of a building, where apparently it had fallen through fear and exhaustion,” author William Willis wrote in a special edition of the Portland Transcript, published July 14.

The fire gained strength as it moved to Cotton and Center streets, where it approached the business center.

In addition to a scarce water supply, a lack of reliable communication also hampered efforts to stop the fire’s march across the city.

According to Fire Department records, Portland Steam Engine Co. 2 had just gotten set up on Commercial Street at Brown’s Wharf, when the crew was suddenly called away to Union Street, where the Bond & Merrill Shop was believed to be ablaze. After seeing no fire, they charged back to Free and Center streets, but quickly ran out of water. Crews moved again to Monument Square, where they were able to contain the blaze on its western edge.

But the fire marched northeastward.

As the wind raged, so did the noise of the speeding inferno.

“A great roaring was heard afar off, and coming nearer and nearer – the door-steps and house-tops began to be crowded with breathless listeners,” Neal wrote. “The heavens gathered blackness, and a hurricane of fire swept over the city, carrying cinders and blazing fragments of wood far into the country, and actually firing houses on North Street, and more than a mile away, and soon after, in Falmouth, five miles distant.”

Willis also noted the thunderous flames: “The fire (advanced) with a roar, like that of some infuriating monster, sending before it, as the fiery breath of its nostrils, a tempest of red-hot cinders, each one an incendiary and messenger of destruction.”

The flames largely stayed to the north of Fore Street, but would eventually extend as far north as Oxford Street in what is now Bayside and as far east as Mountfort and North streets on Munjoy Hill.

Throughout the night, the typically dark skies of Portland were alive with fire. According to one account, the ominous orange glow could be seen from Jonesport, roughly 135 nautical miles to the northeast.

By 10 p.m., the fire reached a block of brick buildings on Market and Middle streets. Many believed the worst was over – that the brick walls would stop the flames dead in their place. But heat and flames infiltrated the barrier, melting the iron shutters covering the windows and gutting the buildings, before devouring another densely populated neighborhood en route to Washington Avenue.

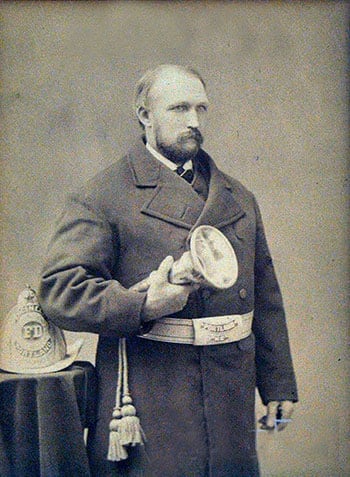

First Assistant Engineer Frank Merrill, shown here several years after the fire, dodged a volley of fireworks that were set off as a toy store burned. Photo courtesy of the Portland Veteran Firemen’s Association collection at the Portland Fire Museum.

Fireman Frank Merrill had taken up a position at Exchange and Federal streets, after working for hours to contain the fire down on Commercial Street. While laying hose to fight the fire in the center of the business district, a large cache of fireworks at the Charles Day Toy Store suddenly ignited.

“A big rocket whizzed over my head, and there came a regular volley,” Merrill recounted 30 years later. “Perhaps you think I stayed there, but I didn’t. I laid down that pipe and I ran. That was all I could do.”

Merrill and his crew then chased the fire to Cumberland and Pearl. Crews thought they had finally contained the fire, but it leapt across Congress Street, igniting the dome of the new City Hall, which had just been built two years before. It too was believed to be fireproof.

The fire spread even more quickly among the random assemblage of wooden homes to the east of Market Street. Houses were crammed in, side-by-side, extending as far as Fore and India streets. The narrow neighborhood of dirt lanes had become littered with possessions that were brought into the street in an attempt to save them, but instead became bridges that carried the fire deeper into the city.

Fire ignites Fourth of July fireworks on Middle Street in this painting by George Frederick Morse. Photo by Derek Davis/Staff Photographer. Courtesy of collections of Maine Memory Network.

Hannah Thurlow, the 91-year-old Fore Street resident, was carried away to safety. It must have been déjà vu for Thurlow, who was also carried to safety as an infant in 1775 when Portland was bombarded by a fleet of British naval vessels.

The streets were crowded with people with blackened faces and clothes scorched by burning embers, frantically calling for help – whether it was to find missing children or move their belongings. Church steeples collapsed. Slabs of stone and granite fell from the sky.

Some hurried away from the fire with their possessions in wheelbarrows. Others carried couches on their backs. One man mistakenly cleaned out his neighbor’s apartment, instead of his own. Another was observed driving a horse-drawn carriage full of furniture that had caught fire without him knowing it.

Local merchants removed as much of their inventory as possible. Some took their goods down to the wharves, only to have their supplies stolen by opportunistic vagrants and thieves who snatched up items as quickly as they were put down.

Some carriage men charged exorbitant fees to shuttle people and belongings to safety.

“These scenes amid this crowded population, thus hotly assaulted by fire, irresistibly marching on, were agonizing to look upon,” the Portland Transcript reported shortly after the fire. “The sick were carried from their burning homes on their beds. Distracted men, women and children, ran hither and thither shouting and imploring help.”

Fire Engineer Alfred Wiggin, left, poses in this 1869 photo with a steam engine similar to those used to battle the Great Fire. Photo courtesy of the Portland Veteran Firemen’s Association collection at the Portland Fire Museum.

Extraordinary efforts were made to stop the blaze. About 50 buildings were intentionally blown up using kegs of gunpowder including one at Cumberland and Pearl. A group of 100 men used large hooks and ropes to physically pull down wooden buildings on Commercial Street, which, along with most of the buildings on the southern side of Fore Street, went largely unscathed. The goal was to create a firebreak to stop the advancing inferno.

Fire engineer Alfred Wiggin and his crew were forced to flee their position at Cumberland and Franklin streets, when the heat fractured the thick ornamental glass lantern on the steam engine. The crew had been fighting at the western and northern edges all evening, moving from one reservoir and cistern to the next, pumping each one dry.

“When that heavy glass was splintered I thought it was time to get out of that place and we hitched up,” Wiggin recalled 30 years later. “While horses were being put in, we had to brush the sparks off their backs.”

As the fire swept across the city, residents fled to the city pasture land on the slope of Munjoy Hill and to the Eastern Cemetery, where they found a sanctuary among the grassy expanse and headstones of the dead.

Writer Charles Illsley made his way to the Eastern Cemetery at around 3 a.m. He observed the huddled masses of newly homeless Portlanders, as the mile-long fire continued to rage before their disbelieving eyes.

“Houseless men, women, and children were seated in scattered groups about the place, looking as if the tenants of the tombs and graves had come forth to witness the appalling scene. Overhead, lurid clouds of smoke rolled wildly away toward the north, whence descended an incessant shower of fiery rain.”

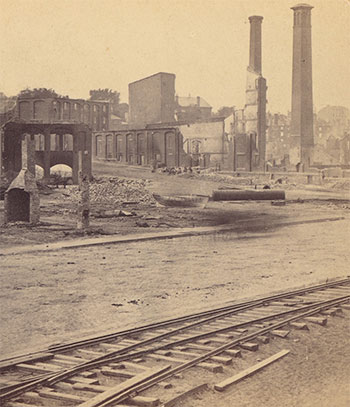

York and Danforth streets, view of the rear of the Portland Sugar House after the fire. Photograph by J.A. Whipple. Photo courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Among the cemetery refugees was amateur painter G. Frederick Morse, who set up his easel and painted throughout the night. By dawn, Morse had produced four stunning oil paintings on canvas. Bright orange flames are contrasted with a black masses, illustrating the desperate confusion of the night.

The conflagration eventually burned itself out on the sand and gravel slopes along North Street on Munjoy Hill.

“As the night wore away, the fire died out for want of further material, the exhausted people lay down in the streets to sleep, some beneath the tottering walls, some in coffins saved from the fire, and others on the remains of their household furniture,” Willis wrote.

As the sun rose on July 5, one of the most beautiful cities in the union had been reduced to smoldering piles of rubble. Brick chimneys, teetering over cellars full of ash and debris, were the only relics of once densely populated neighborhoods. Jagged walls of multistory brick buildings stood hauntingly amid the ruins of a once bustling urban center.

“Portland looked like the bombing of Dredsen in World War II,” said Adams, the local historian.

More than 10,000 people were homeless and hungry. Roughly 200 acres – one-third of the city – was in ruins, including half of the city’s 200 manufacturing companies. All of the newspaper offices, many of which were on Exchange Street, were destroyed, and it would take days for regular printing to resume.

“Beautiful gardens were laid waste, and elegant homes became a scene of desolation,” The Portland Transcript reported a week later. “The whole area was honeycombed with cellars partially filled with fallen bricks, while above them rose the naked chimneys, a forest of brick in place of the once beautiful shade trees whose blackened trunks only remained.”

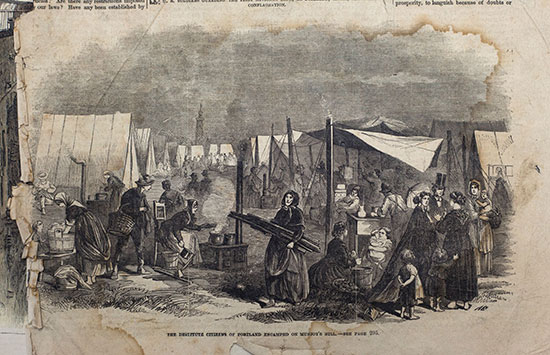

Before long, a tent city, comprised of 1,500 military-issued shelters, sprung up mostly on the lower banks of Munjoy Hill, between the Observatory and the Eastern Cemetery. Other tents were set up in Deering pasture, on Pine Street and in Cape Elizabeth, in an area that is today South Portland.

Photographs taken days after the fire show neatly arranged lines of tall white tents along the hillside. An artist’s rendering in the July 28, 1866, edition of Harper’s Weekly depicts tents set up among the ruins. Some of the tents had wooden floors with bunks and cooking stoves and furniture outside, while others were much more modest.

Cauldrons of soup, pots of coffee, barrels of bread and other food were offered for the destitute at the old City Hall in Monument Square and at the Ward Room on Munjoy Hill. Most of the provisions were donated by nearby towns. Some of the homeless relied on soup lines for nearly a year.

“Destitute citizens of Portland” are shown encamped on Munjoy Hill in an image from New York-based Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Image courtesy of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

A writer for Harper’s Weekly described the scene: “Here all day long were men, women, and children, Americans, Germans, and Irish, all huddled together, each awaiting their food, which had been sent from various quarters, and which they received with hearty thanks and joyful countenances.”

The Brown family’s losses were reported to total between $357,000 and $700,000, or between $8 million and $17 million in today’s dollars. The Portland Transcript declared they were among the largest in U.S. history up to that point.

But the family immediately looked to the future. And Portland, as it had done before, would rebuild.

“We have not lost our courage or our faith,” John Marshall Brown said in his letter to Alida. “Father begins tomorrow to build some stores on the burn lots & as soon as we can clear away the debris we shall start another Sugar House.”

The Great Fire of 1866

The Night Portland Burned

A firecracker and a pile of wood shavings turn a day of celebration into a “frightful calamity.”

MorePortland's Plea is Answered

Before the smoldering ruins of Portland’s Great Fire had cooled, city leaders were calling on communities near and far to send food, shelter and money to rebuild.

More

Tell your friends