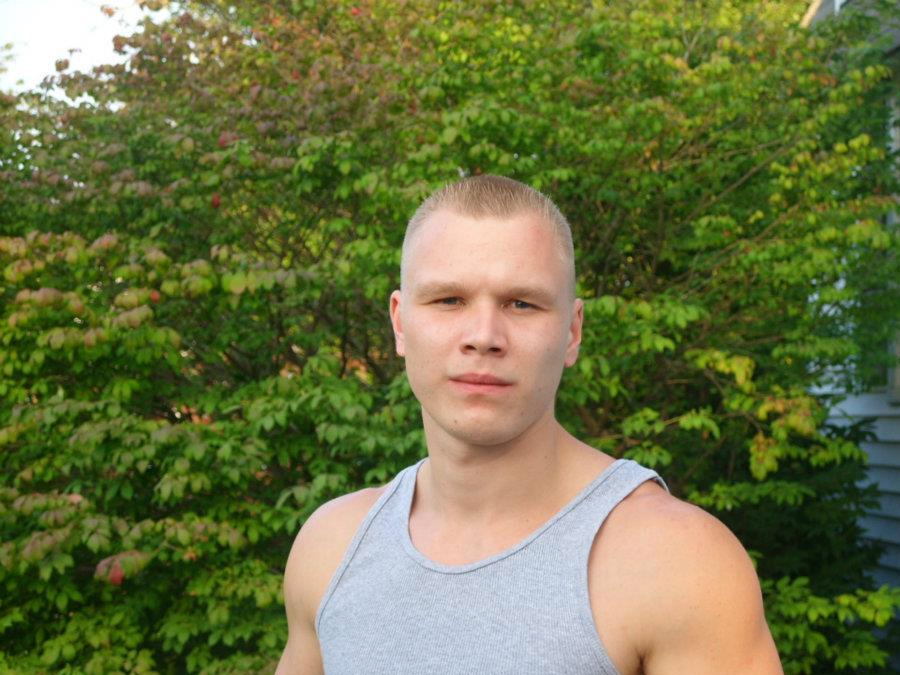

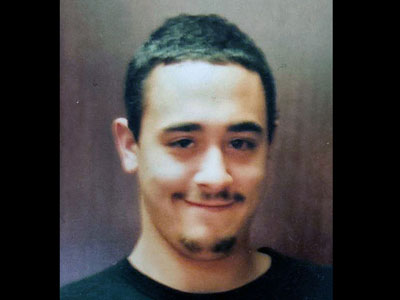

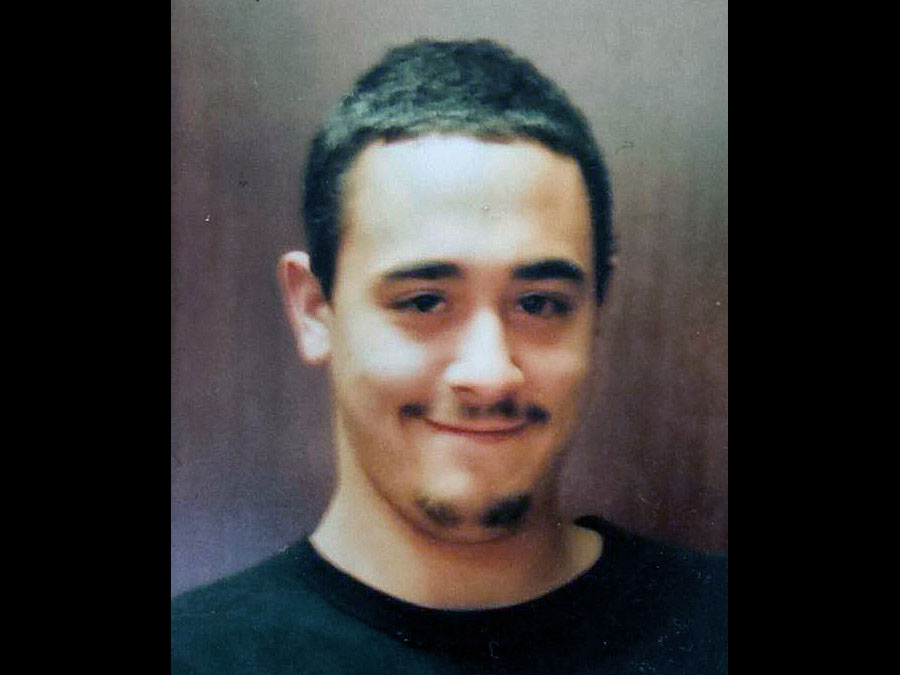

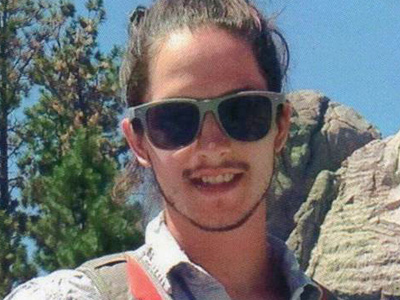

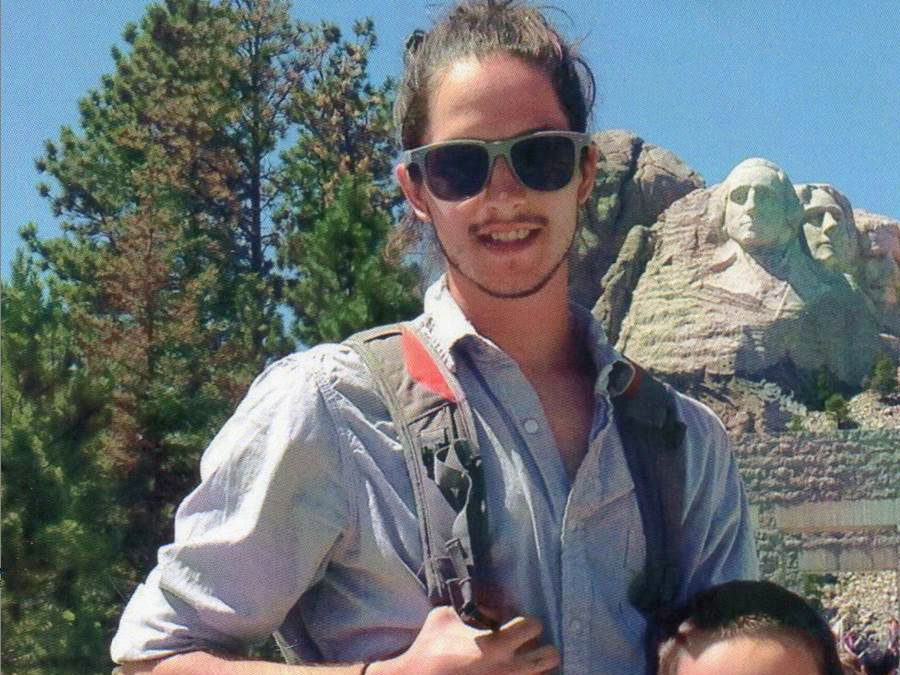

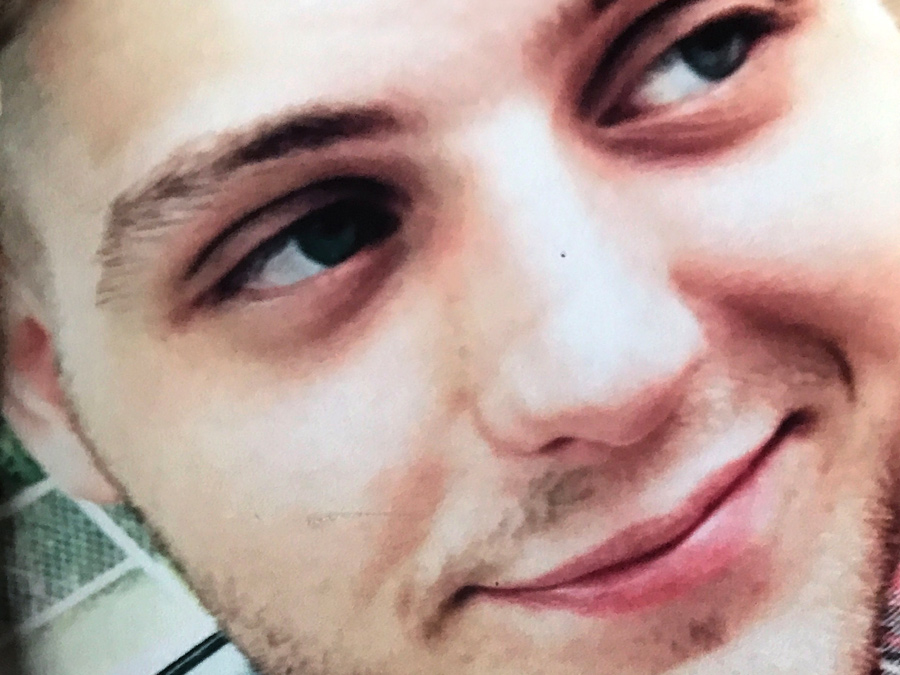

A gifted competitor with a Major League Baseball dream

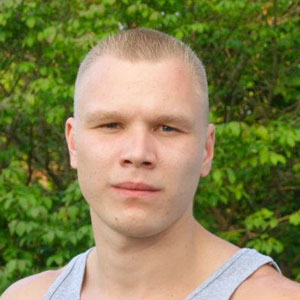

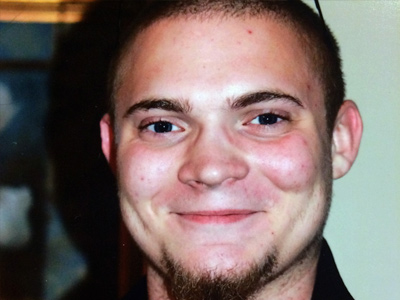

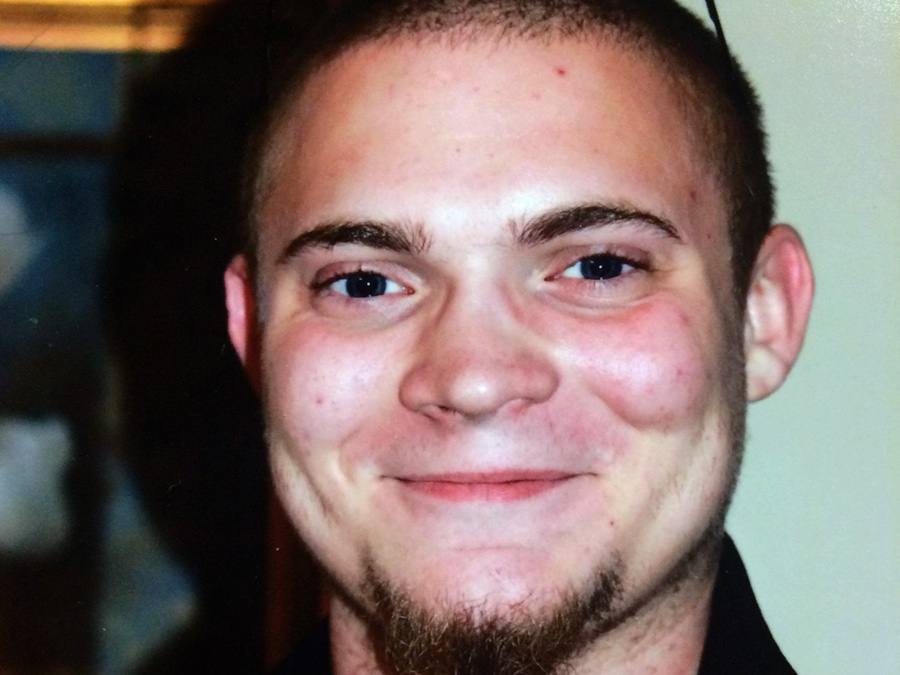

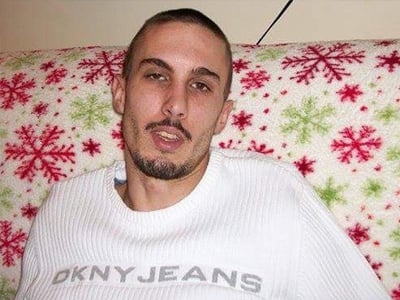

Nick Douglass was going to pitch in the Major Leagues. That was his dream.

“The third grade,” said his mother, Patty Dumont of Minot. “I remember going to his teacher conference. They had asked him, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ His answer was, ‘MLB player.’ They asked, ‘What do you want to do in life?’ ‘MLB,’ he said.

“Everything in his life was MLB. And they said it was unrealistic, that he should have another goal. He said, ‘No, that is my goal.’”

Nick could throw a baseball. He was a standout athlete at Poland High School and would pitch two years for Ed Flaherty at the University of Southern Maine, in 2011 and 2012, after transferring from Franklin Pierce University in New Hampshire. He struck out 122 batters in 87 2/3 innings for the Huskies. He also played independent ball for two years, pitching for the Old Orchard Beach Surge in 2015 until an elbow injury ended his pitching career.

“Nick loved the competition,” said Dumont. “If there was something he couldn’t do, he would try it because that was in his makeup.”

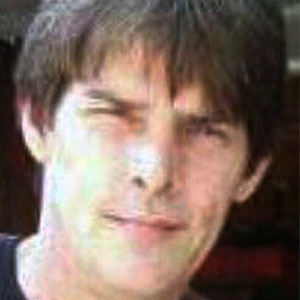

That made him a leader on every team he played on. Flaherty called him "one of the most competitive kids I ever had.”

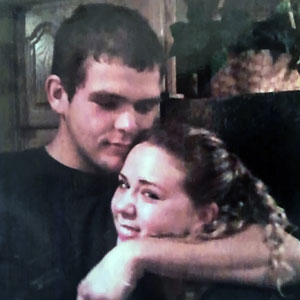

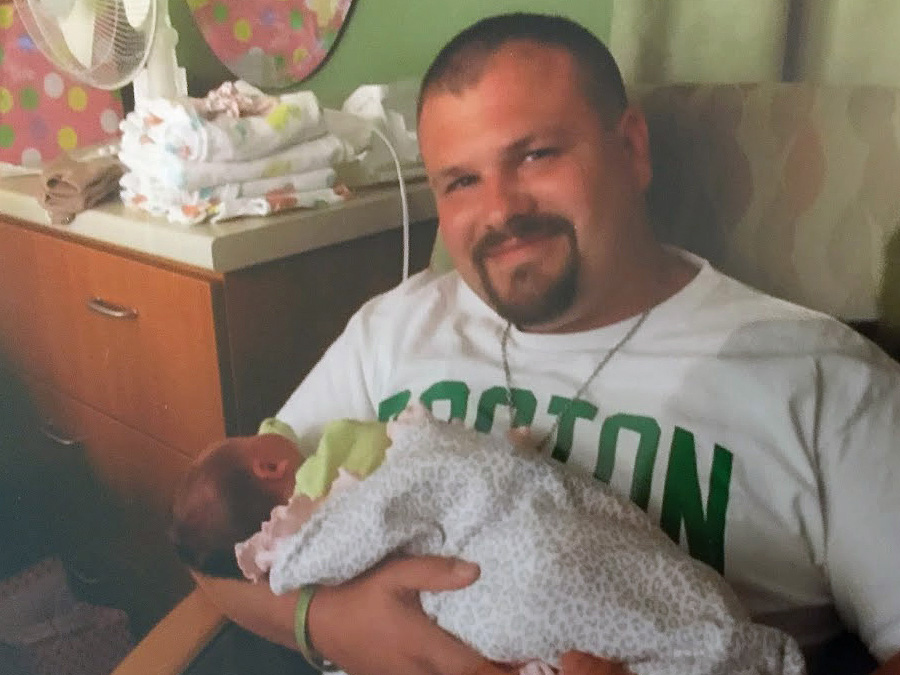

Nick’s mother believes he began using drugs at Franklin Pierce, where he began suffering anxiety after the death of a close friend and teammate. Nick became addicted to heroin. He went through detox twice and got into a residential treatment program in Florida. But he relapsed and died of an overdose on Nov. 25, 2015. He was 25.

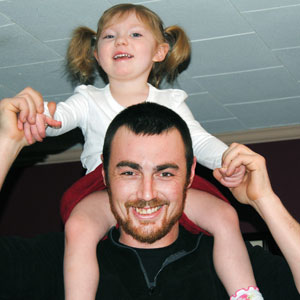

His mother remembers him as always active and involved in some sport, whether it was competitive or friendly, such as disc golf. “He never sat down,” she said. “Unless he was playing his Xbox.”

He liked to have fun, too. “He was a jokester, a prankster who wanted to be the life of the party,” she said.

And, his friends noted, he was compassionate and loyal. While he was a gifted athlete, he befriended everyone in high school.

“He was loved by everybody,” said Dumont. “He had an infectious smile. He liked everybody. He stuck up for everyone. He was a jock, but he had friends who weren’t. And he would stick up for them. If one of his best friends, or a teammate, was picking on some scrawny kid from his English class, he would stick up for them.”

– MIKE LOWE